Society and philosophy in Africa

The location of philosophy in African societies

At present, in continental Africa and the Black Diaspora, many fundamental topics are being engaged: Pan-African events of extreme importance have taken place; PANAFEST was hosted by Ghana some few months ago; the year of return was celebrated in 2019 in Ghana; and publications and discussions that take a critical look at the future of Africa and also the Black Diaspora are regularly organized. That leads me to devote some time and energy to the journey of Africa and the key factors that influenced that march from the last days of colonial rule to this period of postmodernism, globalization and Afri(o)futurism.

Kwame Nkrumah’s consciencism and its relevance

Conscienism was published by the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, in 1964 and it lays down his introduction to philosophy in the US. In the book, Nkrumah ponders over the conscience and state of mind of the African, how the identity of the African was constructed, the impact that the African produced by such circumstances had on the education, economy, politics and culture of their country. Nkrumah’s reflections end with the way froward for Africa, the clarion call that is supposed to wake Africans from their slumber.

It might be necessary at this point to mention a notion which is crucial in the discussion on Africa: the African world view and African philosophy. One often encounters the statement that the view or concept that the African has of the world is different from that of the West because the former is cyclical while the latter is linear. In other words, the living and the dead co-habit or co-exist in Africa, a view that has been propounded by several African novelists and poets, explicitly and implicitly like the Senegalese Birago Diop and the Nigerian Wole Soyinka. Spirits, ancestors, the connection between the African and their surroundings, living milieu and environment is very strong, sacrosanct, sincerely and deeply revered. On the other hand, the western world view is generally known to be linear and Aristotelian sometimes, which means that things occur and then people move to the next stage, a new period or era. That tallies with the saying, “one does not bathe twice in the same river”, which means that time moves forward and with it, everything marches forward and changes and is replaced by something new which, in its turn, will give way to another entity. Kwame Nkrumah and his Consciencism are relied upon here because of the holistic way in which the African society is looked at.

Africa’s past, present and future

It is impossible to speak about these three stages without taking into consideration education and its forms and roles in Africa. Precolonial Africa had an education that was endogenous and Afromorphous, rooted in the African soil with the main goal of meeting the needs of the African people as scholars like Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Amadou Hampâté Bâ and Nkrumah posit. The intrusion of western education truncated the organic evolution of African society and its key machineries like education, governance, belief system, etc. Concretely, that manifested through the elevation of European values and the relegation of African values to the level of backwardness and savagery, an “appalling stage” that Africans are urged to move away form, and to leave far behind in order to embrace the western ones. In Consciencism, Nkrumah paints the “thirst” for western education and the vigorous move to grab that education in these terms: The yearning for formal education, which African students could only satisfy at great cost of effort, will, and sacrifice, was hemmed in within the confines of the colonial system. Recoiling from this straight-jacketing, a number of us tried to study at centres outside the metropolis of our administering power and opted for western education in the USA. The subsequent demonization of Africa and her realities is couched in the following lines by Nkrumah, “The colonized African student, whose roots in his own society are systematically starved of sustenance, is introduced to Greek and Roman history, the cradle history of modern Europe, and he is encouraged to treat this portion of the story of man together with the subsequent history of Europe as the only human history that has human value.” That explains the birth of the alienated African whose distinct feature is confusion, or in subtle words, double consciousness and hybridity.

The flaws of western philosophy and how it generated harm in Africa

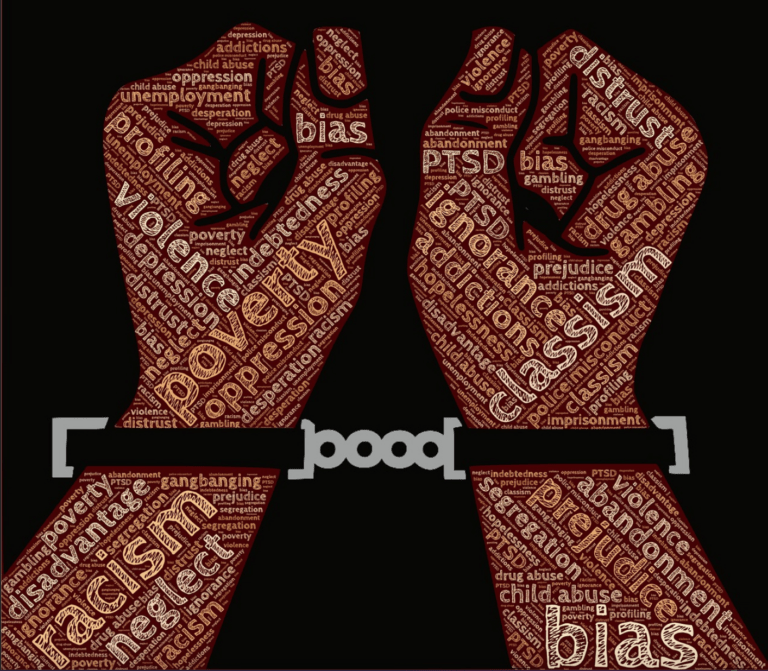

While African[a] philosophy can be formally defined as a critical thinking by Africans and people of African descent on their experiences of reality, western philosophy is divorced from human life. It becomes so abstract in certain western universities as to bring its practitioners under the suspicion of being “taxidermists” of concepts. And yet the early history of philosophy shows it to have had living roots in human life and human society. In other words, western philosophy initially functioned the way African philosophy did vis à vis the society or milieu they were basking in. So the suppression of that two-way interaction or flow between philosophy and the social context is the origin of the woes of Africa and, by extension, the Black diasporan. The crucial function of that osmosis can be explained this way: social milieu affects the content of philosophy, and the content of philosophy seeks to affect social milieu, either by confirming it or by opposing it. In either case, philosophy implies something of the nature of an ideology. In the case where the philosophy confirms a social milieu, it implies something of the ideology of that society. Once that harmony between philosophy, ideology and society is eliminated, we witness an extremely disastrous situation where people do not walk the talk. Lack of sincerity and honesty settle and thought and practice become two entities or practices that have no connection. Nkrumah posits that, “Practice without thought is blind; thought without practice is empty”. The coup de grâce that the blind transposition of the western political system delivered can be captured in these words: the principles which inform capitalism – which itself is the core of western politico-social life – are in conflict with the socialist egalitarianism of the traditional African society. The trouble in /of African countries today can be traced to that incident that occurred in the course of the interaction or encounter between Africa and Europe. The conscience, identity, state of mind, governance system of Africa changed for the worse by the time pseudo-independence was given to African nation states and the previous harmonious and tranquil peace and development were taken away, forever. One book that addresses those facts in a clear and scientific manner is Kwame Nkrumah’s Consciencism which remains – with its numerous analyses and interpretation – the key to understanding the present situation of Africa.

Moussa Traoré is Associate Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.