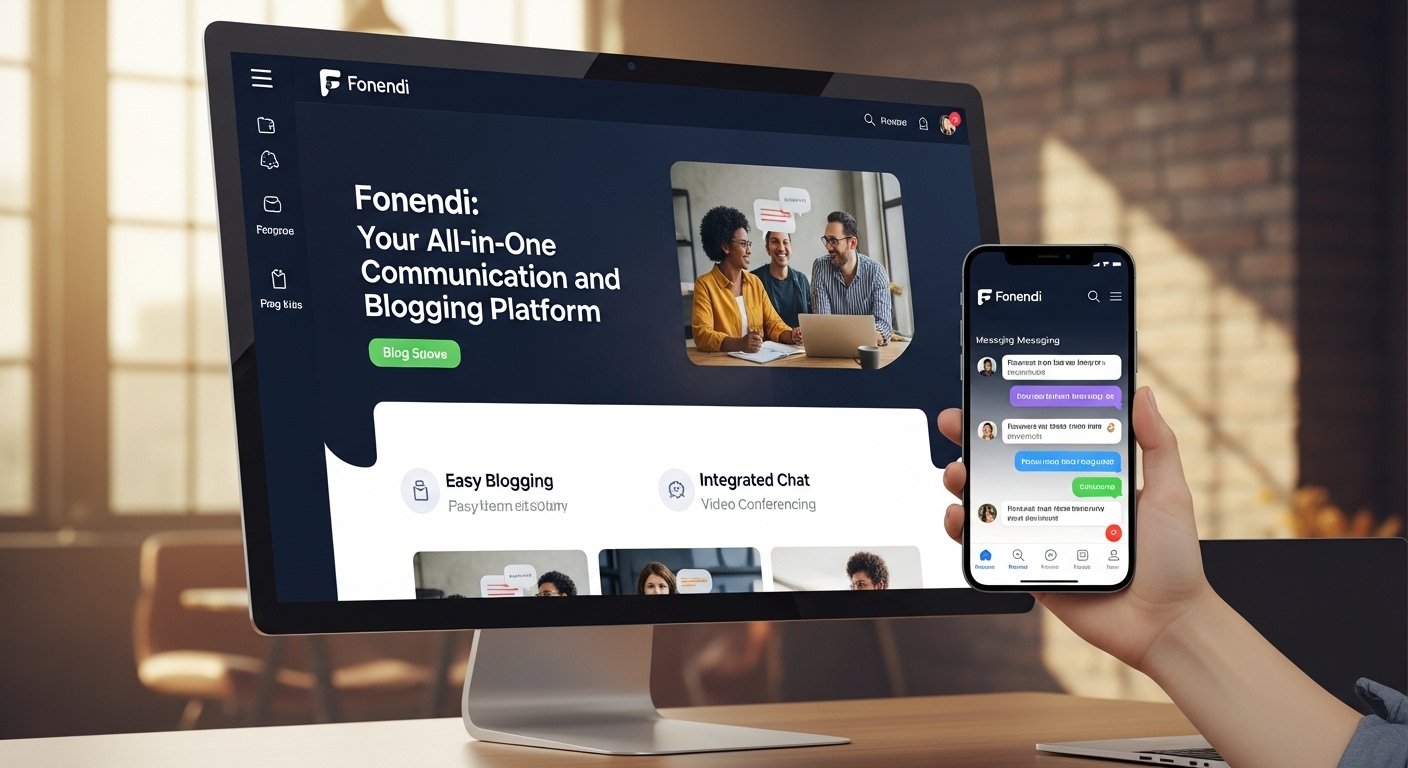

In today’s fast-paced digital world, managing communication, content creation, and online presence effectively is more important than ever. Whether you are a professional, a blogger, or simply someone who wants to stay connected, having the right platform can make all the difference. Fonendi: Your All-in-One Communication and Blogging Platform offers a versatile solution designed to meet these exact needs. Launched in the early 2020s, Fonendi has quickly become a go-to digital platform for individuals and professionals seeking seamless communication and robust content creation tools.

What is Fonendi?

Fonendi is a multi-functional digital platform that integrates messaging, calling, blogging, and content creation in one streamlined interface. Unlike traditional messaging apps that focus solely on conversations, Fonendi goes a step further by providing innovative tools for content creators, bloggers, and professionals. It serves as a communication hub and a digital content platform, allowing users to manage both personal and professional interactions without switching between multiple apps.

At its core, Fonendi is designed to simplify communication while enhancing productivity. Its user-friendly interface ensures that even those who are not tech-savvy can navigate the platform effortlessly. From private messaging and group calls to publishing blog posts and tracking content performance, Fonendi is built to serve as a one-stop solution for modern digital needs.

Key Features of Fonendi

1. Messaging and Calling

Fonendi’s messaging feature is highly versatile, offering both private and group chats. Users can send text messages, images, videos, and even documents, all within a secure environment. In addition, the platform’s integrated calling features allow users to make high-quality voice and video calls. Whether it’s a professional meeting or a casual conversation with friends, Fonendi ensures smooth, uninterrupted communication.

2. Content Creation Tools

Fonendi is not just about messaging. It provides powerful content creation tools that allow bloggers and creators to write, edit, and publish content directly on the platform. Its advanced editor supports multimedia integration, enabling users to add images, videos, and interactive elements to their posts. This makes Fonendi a true digital content platform, where creators can focus on producing engaging and visually appealing content without relying on third-party tools.

3. Analytics and Insights

Understanding your audience is crucial for content creators, and Fonendi excels in this area. The platform offers detailed analytics that tracks engagement, views, shares, and other key metrics. This data-driven approach helps users refine their content strategies, ensuring that every post resonates with their audience. For bloggers and professionals alike, these insights can be the difference between mediocre and exceptional online engagement.

4. Multi-Platform Accessibility

Fonendi is accessible across various devices, including smartphones, tablets, and desktops. This ensures that users can stay connected and manage their content from anywhere, at any time. Whether you are traveling, working remotely, or at home, Fonendi keeps you in touch with your network and your audience seamlessly.

5. Secure and Private

Privacy and security are top priorities in the digital age, and Fonendi takes this seriously. The platform uses end-to-end encryption for messages and calls, ensuring that user communications remain private. Additionally, content created on Fonendi is protected against unauthorized access, giving creators peace of mind as they share their work online.

Why Choose Fonendi?

Streamlined Communication

Many people use multiple apps to chat, call, and manage content. Fonendi eliminates this hassle by integrating all these functions into one platform. Users no longer need to juggle between a messaging app, a blogging tool, and analytics software. This streamlining not only saves time but also improves productivity.

Ideal for Bloggers and Creators

Fonendi is designed with content creators in mind. Its editing tools, multimedia integration, and analytics make it easy to create, publish, and track content performance. For bloggers, the platform offers an intuitive interface that allows them to focus on storytelling and engagement rather than technical complexities.

Professional and Personal Use

Whether you are a professional managing team communications or an individual staying in touch with friends and family, Fonendi caters to all use cases. Its versatility makes it suitable for small businesses, freelancers, and large teams alike. By combining messaging, calling, and content creation, Fonendi ensures that users can handle multiple tasks without switching platforms.

Community and Collaboration

Fonendi encourages collaboration by supporting group chats, team calls, and shared content spaces. Creators can work together on projects, brainstorm ideas, and provide feedback directly within the platform. This community-oriented approach fosters collaboration and strengthens connections among users.

How Fonendi Stands Out

While there are many communication and blogging platforms available today, Fonendi distinguishes itself through its integration, simplicity, and versatility. Unlike apps that focus solely on one aspect of digital life, Fonendi combines multiple functions without overwhelming the user. Its clean interface, powerful tools, and secure environment make it a preferred choice for both casual and professional users.

Additionally, the platform is constantly evolving. Updates frequently bring new features, improved performance, and enhanced security measures. This commitment to innovation ensures that Fonendi remains relevant in the ever-changing digital landscape.

Getting Started with Fonendi

Starting with Fonendi is straightforward. Users can sign up with their email or mobile number, set up a profile, and begin exploring the platform’s features. Whether you want to send a message, create a blog post, or schedule a group call, Fonendi’s intuitive interface guides you through the process effortlessly.

For creators, Fonendi provides tutorials and tips to maximize the platform’s potential. From writing engaging blog posts to using analytics effectively, these resources help users make the most of their digital presence.

Conclusion

In a world where digital communication and content creation are integral to personal and professional success, having a reliable, versatile platform is essential. Fonendi: Your All-in-One Communication and Blogging Platform offers exactly that—combining messaging, calling, blogging, content creation, and analytics in one secure and user-friendly environment. Its versatility makes it ideal for individuals, creators, and professionals looking to streamline their digital activities and enhance productivity.

By integrating communication and content tools, Fonendi not only saves time but also empowers users to connect, create, and grow online. Whether you are a blogger seeking to engage an audience, a professional managing team interactions, or simply someone who values seamless communication, Fonendi provides the tools and features needed to thrive in today’s digital world.

With its innovative approach, robust features, and commitment to user security, Fonendi is redefining the way people communicate and create online. It is more than just a platform—it is a digital hub where ideas, conversations, and creativity converge. For anyone looking to elevate their digital presence, Fonendi is the ultimate all-in-one solution.