French colonial fallacies continue to influence contemporary scholarship

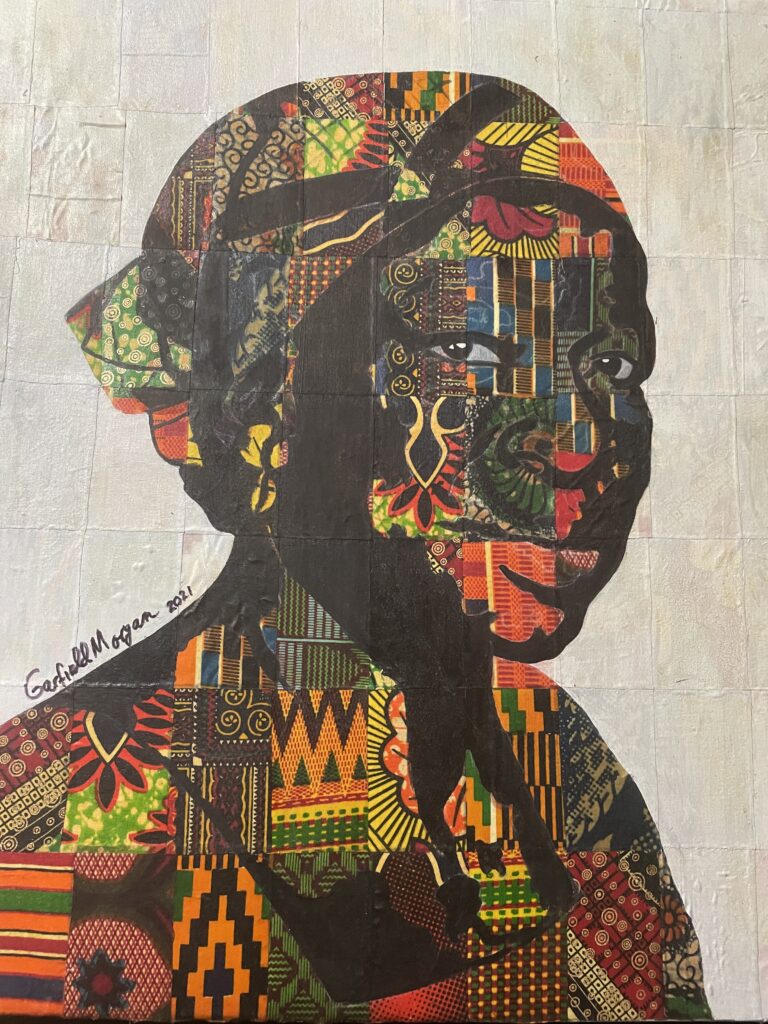

Before western countries created hybridization through their presence in Africa, Asia, the Americas, the Caribbean and so on, one could find societies in those lands that were living with a considerable level of composure, tranquility, and in harmony with their surroundings. Examples would be the native American societies before Europeans waged war against them to marginalize them, take their lands away and force them into the confines of history. In Africa, many communities that are now bearing the brunt of the environmental crisis are advocating the return of indigenous traditional knowledge (ITK) – a set of rules that encourage the preservation of the environment. Communalism was also a core values of those societies. The relentless drive to carve out and own property was almost nonexistent. In a nutshell, pre-colonial societies functioned and relied on these rules and demonstrated very little bellicose tendencies. The conquest of territories was a reality but the peaceful inclination behind such acts cannot be compared to the gluttonous and ferocious urge that guided confrontations and wars in the history of Europe.

Many scholars maintain that Europe invented the “non-European territories and people(s). Hegemonic western nations pillaged the material, cultural and intellectual resources, wealth and property of the nations that had been prospering in their own cultures and civilizations. Scientific sources record that in order to “cripple” the African, Asian an American societies that they encountered and admired because of their sophisticated levels of advancement, the West had to brand them as barbaric, backward, savage and undeveloped. That is the essence of the rapport that was posed between Greece and Africa, to mention just one example. Cheick Anta Diop, Theophile Obenga, Joseph Ki-Zerbo and many who are often referred to as ‘Afrocentic’ or ‘Africentric’ demonstrated that process. Western ‘elites’ acquired knowledge from Africa and committed a double crime by stating the lie that they had produced that knowledge, and they also emptied the repositories of world scholarship that were situated in Africa of their content. Once Europeans knew that this knowledge was safely in their possession, the repositories were razed.

Literacy and socio-political advantage or domination are very important in such contexts, and education is key in the existence and evolution of a society. Hegemonic Europeans created an African whom they called inferior and perpetuated that belief. So, children were taught what society wanted them to know and to believe. The inferiority of certain races compared to others was presented as an irrefutable truth that every European child, as well as Black children who attended western schools, learnt.

I will mention one instance which speaks volumes. In French culture and French literacy, La Fontaine (whose full name is Jean de la Fontaine) is known to be the creator of hundreds of fables that are used as classic literary pieces in teaching reading, French culture and, certainly, writing. Africa boasts of prolific research centres like Afrique Résurrection (AR), a pan-African media for the new generation, founded by the young revolutionary anti-capitalist and unbowed young French man of African descent, Kemi SEBA. Investigations and research conducted by that centre unearthed that this icon of which the French are so proud, because it is the foundation of the whole French language and culture, “The Fables of La Fontaine”, does not have a French origin, but rather an African one.

Aesop is the man at the centre of the discussion, he was known to be a Black man, an African from Sudan who was dark skinned, with thick lips, dark hair, flat nose and all the attributes of the Black African. Afrique Résurrection portrays him exactly this way: Aesop is “620–564 BCE; formerly rendered as Æsop, he was a Greek fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as Aesop’s Fables. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales credited to him were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day. Many of the tales associated with him are characterized by anthropomorphic animal characters”. Aristotle and Herodotus state that “Aesop was a slave in Samos; that his slave masters were first a man named Xanthus, and then a man named Iadmon; that he must eventually have been freed, since he argued as an advocate for a wealthy Samian; and that he met his end in the city of Delphi”. Both camps intersect on one point: Aesop was Black, captured and enslaved, he found himself in Greece and introduced an art or genre that was new there: the fables. That earned him a reputation and he was freed for his intelligence. Herodotus calls Aesop a “writer of fables” and Aristophanes speaks of “reading” Aesop and that reveals the scholarship that this Black man produced. Lilian Thuram sheds more light on his African origin in her book Mes étoiles noires (My Black Stars, 2009).

On the other hand, Jean de la Fontaine was born in 1621 and was revered as ‘one of the most famous and popular writers of his time and is best known for his work Fables Choisies’. No mention is made of any inspiration of La Fontaine by Aesop. What we often stumble on is comparisons that reveal similarities between the fables of La Fontaine and those of Aesop. The following demonstrates the very close similarities between the stories of the two authors.

‘The Hen That Laid he Eggs of Gold’ by Jean de La Fontaine tells the story of avarice in which wanting it all results in losing it all. He told the fable of a man who owned a chicken who would lay a golden egg each day. Deciding that inside her she must hold a treasure-house of gold the man kills and opens her. He finds she is no different from other hens on the inside.

Aesop, to whom the story of ‘The Man and the Golden Eggs’ is attributed, relates that a man had a hen that laid a golden egg for him each and every day. The man was not satisfied with this daily profit, and instead he foolishly grasped for more. Expecting to find a treasure inside, the man slaughtered the hen. When he found that the hen did not have a treasure inside her after all, he remarked to himself, “While chasing after hopes of a treasure, I lost the profit I held in my hands!”

It would be very profitable to deepen such research, and try to find out if inspiration or influences of any type existed between Aesop and Jean de La Fontaine, but such research is scanty and not encouraged, almost non -existent since it is generally believed (unfortunately) that nothing good comes from Africa, from Blacks. So, a French fabulist could not have been inspired by a Black or someone of Black descent.

Moussa Traoré is Associate Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.