What can online exhibitions do?

Recently, a new, online exhibition of work by Jamaican artists was launched under the title Rupture: Interventions of Possibility. It features work by Katrina Coombs, Zachary Fabri, Timothy Yanick Hunter, Zinzi Minott, Oneika Russell, and Soshanna Weinberger, and was curated by Gervais Marsh, an art writer and curator of Jamaican descent, and Petrina Dacres, the head of the Art History Department at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts. The online exhibition takes the form of a rather basic web display, with a page for each participating artist. It is hosted by the Art at a Time Like This curatorial platform and can be found at: https://artatatimelikethis.com/intervention-of-possibility

The exhibition is an initiative of the Jamaica Art Society, a New York City based members’ organization founded by communications specialist and art patron Tiana Webb Evans. This society seeks to promote Jamaican art and artists, in Jamaica and in the diaspora. They have an annual fellowship programme, the In Focus Fellowships, that is open to artists, curators and writers of Jamaican descent and seeks, as the society’s website states, to bring their professional practice “into dialogue with the broader art world through professional mentorship and workshops with our cultural partners”. The nine-month fellowship, which also involves a stipend, culminates in a collaborative project, in this case Rupture: Interventions of Possibility, which features the curators and artists who were part of the 2022 In Focus Fellowship programme.

While the commendable work done by the Jamaica Art Society deserves its own discussion, which I will leave for another occasion, viewing Rupture allowed me to reflect a bit more on the possibilities and limitations of online exhibitions. The pandemic, with its lockdowns and the temporary closure of museums and galleries, led to a marked surge in the production of such exhibitions. This has now subsided but there is no doubt that online exhibitions are here to stay, while the relevant technologies will continue to develop. The question arises how online exhibitions measure up to “real life” exhibitions, however, and what this all means for artists, curators, and their audiences.

The terms virtual and online exhibitions are often used interchangeably but there is a distinction that is worth noting. “Online exhibition” is the more general term, and refers to all exhibitions on internet platforms, while “virtual exhibition” is more specific and suggests an immersive experience, typically in a virtually generated space. Online exhibitions involve a wide range of possibilities. They include: social media, with Instagram as a popular choice; web-based videos, for instance on YouTube or TikTok; a website or website segment, as was done for Rupture; using specialist virtual exhibition platforms, such as ArtSteps; and proprietary designs that can recreate actual exhibition spaces in great detail. Online exhibitions can be very cheap and low-tech, or very sophisticated and costly, when custom immersive design is involved. Online exhibitions now often accompany traditional exhibitions, as a part of how such projects are extended and archived, along with catalogue publications, websites, and video documentaries.

As a curator, I am, however, quite conflicted about virtual exhibitions and, admittedly, still see them as second best to an actual exhibition experience. I have, for instance, been sceptical of the obsession with trying to mimic a real-life exhibition experience, in the form of a “walk” through a virtual space, as this often seems like a frustrating exercise in futility in which more is lost than gained, no matter how fancy the technology may at first appear to be. There is, in fact, a school of thought that online exhibitions should “respect the screen” and capitalize on what can be done that way instead. The curators of Rupture obviously decided to work along those lines.

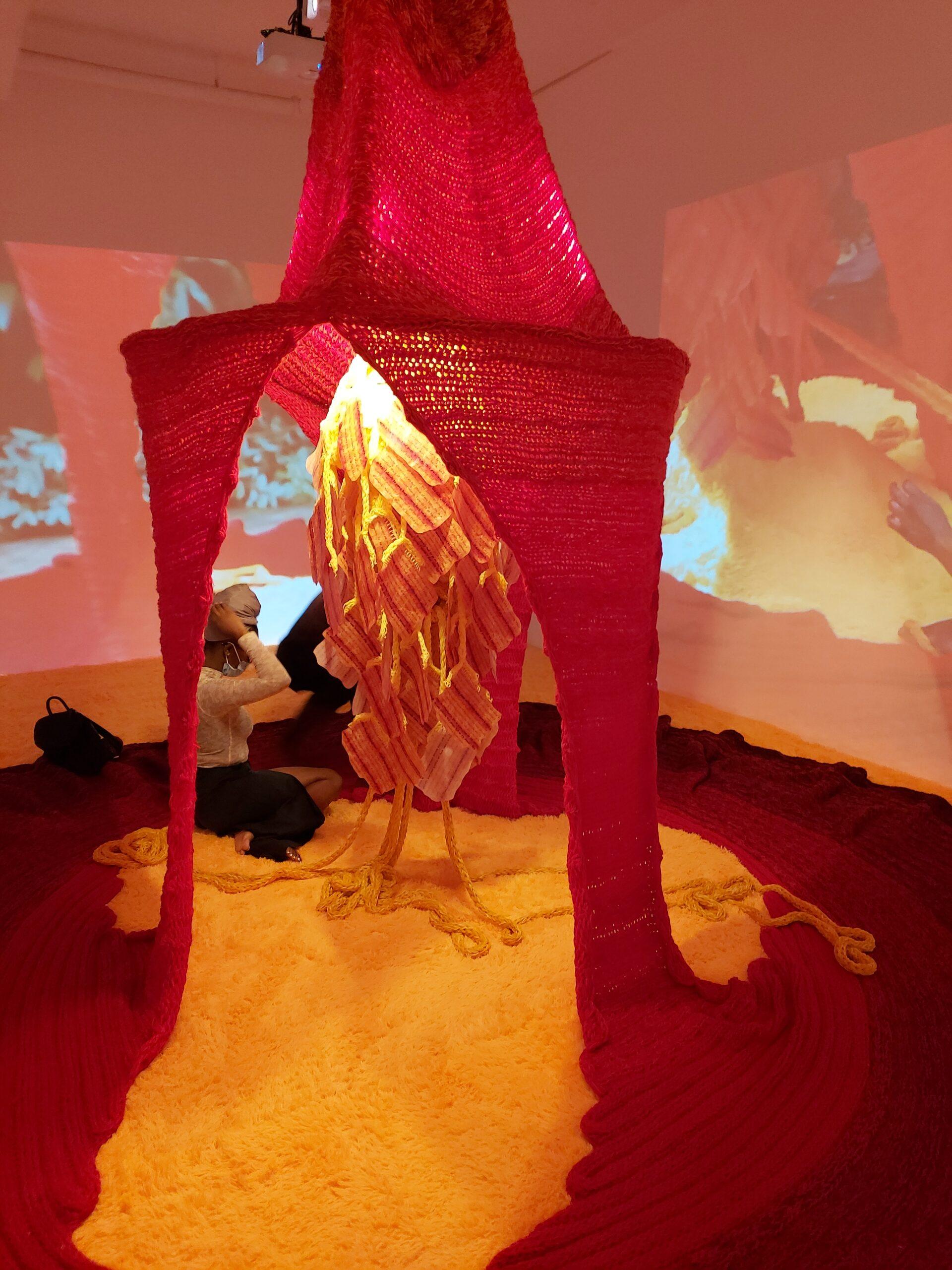

Notwithstanding the format, however, even the most sophisticated online exhibitions still offer a rather sterile, disembodied experience that takes away most of the sensory experience, of the physical presence and materiality, that is so important to interacting with most types of art, reducing the work of art to a mere image in the process. The whole point of Katrina Coombs’ Lifting the Veil (2022) installation, which was one of the most popular works in last year’s Kingston Biennial and which is included in Rupture, is its immersive quality, its open invitation for the viewer to become part of the work. Photographs and video of the work, and the performances that work part of the project, simply cannot not replace that experience.

I am not alone with these anxieties. In fact, they have a long history which predates the internet and online exhibitions. The German thinker Walter Benjamin, in his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935) lamented the loss of “aura” that occurs when works of art are mechanically reproduced and engaged as such reproductions, instead of being experienced in real life, engagement was by means of photography and printing. Online exhibitions build on these technological developments and still raise some of the same questions. Other early commentators, such as the French writer and politician André Malraux, in his essay The Imaginary Museum (1947), recognized the new possibilities, such as the vastly improved popular and scholarly access to art and the ability to make revealing side-by-side comparisons, in art books and slide presentations, between works of art that do not exist in the same space. The modern discipline of art history, which relies heavily on such comparisons, would not exist without mechanical reproduction.

Online exhibitions, which in many ways incarnate Malraux’s “imaginary museum” concept, are indeed a powerful tool to democratise access to art and art exhibitions, and to make these available across space and time (as they usually have a much longer life than traditional exhibitions). They can be held when actual exhibitions are not feasible, which is a very useful solution for cash-strapped artists and art organizations. An actual version of the Rupture exhibition would, for instance, not have been possible without significant expenditure and organizational challenges. Online exhibitions are, by virtue of the technologies involved, also more interactive than traditional exhibitions, ironically leading to a more active visitor experience than many traditional exhibitions.

But online exhibitions also require a different approach to curating. They need to be tailored to what the selected platform can and cannot do and that is where we still have a long way to go. It is for that reason that I have some misgivings about the earlier-mentioned Rupture exhibition, as there appears to be a disconnect between the exhibition concept and the visitor experience, despite an interesting and provocative collection of work and a well-designed website.

The work of an exhibition curator conventionally involves concept development, research, selection and interpretation, which is then conveyed to the resulting exhibition’s audiences through the exhibition design and installation, which choreographs the works of art and accompanying information as well as the visitor experience in a particular space. This choreographing of an integrated experience is a very effective way to communicate those stories, statements and interpretative possibilities that make an exhibition about more than just an attractively presented collection of individual works of art. I am yet to see an online exhibition where such experiential and communicative mechanisms are successfully reproduced.

The point is, of course, that we are still very close to the start of the brave new world of online exhibitions, and it is almost certain that new, immersive technologies will make the experience more wholesome and rewarding. New artistic media, designed for online engagement, are emerging, including the already quite well-known NFTs. In the meantime, however, there needs to be more consideration about the curatorial strategies that work best for online exhibitions and about how curatorial concepts and narratives are best conveyed in the various online formats.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. The second, revised and expanded edition of her best-known book “Caribbean Art” was recently published in the World of Art series of Thames and Hudson. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.