The declining interest in literature and history in African schools

Education cannot be separated from the challenges that a society faces, and Africa is no exception. Colloquia, fora, studies, reports and special consultancies and research teams have pondered over this problem; it really is one because the phenomenon is gaining more and more amplitude and its repercussions are moving from worrisome to openly detrimental. Literature is no more the interest or choice of students in Africa, and history is, to some extent, in the same state. So, what was noticed as an emerging trend in education in Africa is now a full-blown preoccupation.

The lack of interest in the two subjects mentioned above is woeful, and I will stress the case of literature because of my familiarity with that area since I teach that subject. My observations and discussions with colleagues and acquaintances revealed that history is also losing ground in schools. From basic levels of education to higher education, literature is in crisis: enrolment is low, the subject is not given much importance in the school curriculum, students’ performance level is falling and that comes with a cohort of consequences. English as a subject is divided into literature and language and more emphasis is generally laid on language. The declining status of literature is explained as follows. Literature is not the favourite choice of students because it requires much reading, something that they do not like to do since the reading habit started to wane long ago. For decades, the general lamentation of educationalists, parents and concerned citizens is that less and less people like reading and thus we find ourselves in a catch 22. Less reading means less interest in literature and less interest in literature is synonymous with low interest in reading. That, in turn, generates some level of disenchantment in literature instructors and scholars who find themselves witnessing the negligence that their area of expertise suffers. They find themselves with few students to work with and this can cause, in the long run or near future, some degree of employment insecurity and at a larger level, a society which is maimed since it is not abreast with the realities within, it is detached from its present, past and future since reading and information are shunned. We find ourselves with students who possess very limited skills in general knowledge, learners who limit themselves to a mechanical analysis, observation and judgement of the economic and socio-political events determining and affecting their daily life. This, doubtlessly, means being blind to the sine qua non of one’s own existence or life, a form of suicide.

Instructors watch, helpless and worried by the disappearance of the habit of cultural and political debates that were the characteristics of university education some years ago. A case in point is that almost all the leaders in the African countries from the 1960s up to the year 1990 were members of vibrant sociopolitical and literary debate groups or clubs. The Federation of African Students in France, (FEANF) was one such group. These students were really abreast with all factors, events and phenomena that trended in the world in general. They could, therefore, lead or handle impressive analyses or discussions, with facts and figures and draw conclusions related to the advancement of their societies. Reading and, therefore, literature enabled that useful and fine habit, that earmarks a ‘cultured’ citizen or a literate person. The link is, therefore, so obvious, those who like and liked letters and therefore literature and reading are indispensable if our society wants to flourish or progress and Nigerian researcher Eucharia Ugwu (2022) stresses that in these words: “Generally, literature is taught to broaden students’ cultural awareness and knowledge of healthy human values to enhance their language skills; expose them to the beauty and potentials of language; and equip them with the necessary skills for independent thinking and creative writing”. Studying literature empowers one with good language skills. Regardless of the area one was studying, reading, literature, coherent and eloquent speech were part of one’s habits. A science student did not avoid or despise reading, literature, and politics. That in itself is simply a replication of the historical practice of knowledge production and usage. Philosophers and great thinkers in Africa and Greece were well-versed in the Arts and the Sciences: mathematics, rhetoric, politics and wisdom in general were found in the same persons. Aristotle, Plato, Imhotep (father of medicine, architect and statesman) from Egypt, the Senegalese Cheikh Anta Diop (scholar in linguistics, mathematics, etc.) and, more recently, Nigerian Emeagwali (inventor of the formula behind the production of supercomputers, machines that reflect par excellence the combination of Arts and Sciences) are illustrations.

As I mentioned in a previous article, Arts and the Sciences were not separate fields. In order to solve problems in geometry or understand formulae in chemistry and physics, one had to be able to read and understand. The dwindling interest in literature is, therefore, a sudden and new occurrence which does no good to African societies. It produces less impressive graduates who are products of more instruction than education, a generation of learners interested in one thing only: to be able to pass the test that opens the doors of employment. Of course, earning a living and possessing a certain quantity of material wealth is not bad at all, but when material wealth and securing employment become the only interests of citizens, innumerable problems are bound to crop up. Morality, critical thinking and many other virtues that make the difference between humans and inferior beings fade away, tragically.

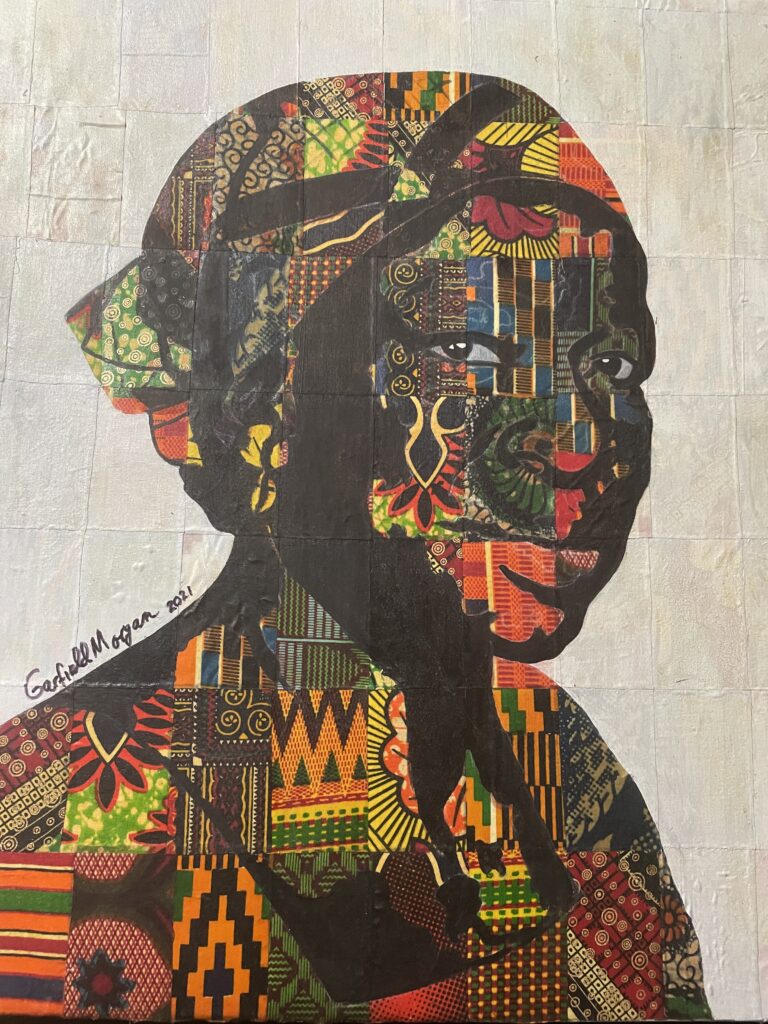

History is also a subject which is losing interest. I was taken aback when I heard that the school curriculum in countries like Nigeria, South and others is moving towards the effacement of history as a subject. In the case of South Africa, the negligence of history connotes an effort towards the oblivion of apartheid and its crimes. In Nigeria, many are the events that marred the past of the country and those events have never had the examination and analysis they deserve: the imperialist-orchestrated Biafran war is one of such cases and it is probably thrown into oblivion because it displays how Nigerians have been manipulated by Western countries. Removing history from the school curriculum represents a challenge to nation building, in a country like Nigeria that used to rely on the harmonious relations between numerous ethnic groups. The past, the present and the future of every society are grounded in the literature and history of or on that society. The surest way to control a country or a continent is to hide literature and history from that people.

The sad coincidence is that this control of the curriculum of schools in Africa can be traced to the 1990s, when the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) of the World Bank became the order of the day. The economy of African states was crippled to a considerable extent through the control of events on the world market and those countries had to seek “assistance” from the World Bank that joyfully pounced on the occasion and offered string-attached assistance which is the recipe for total and long dependence. Such a long dependence and political metamorphosis (that will ultimately lead to instability on the continent) manifested through rigged elections, military leaders turned civilians sticking to power in an attempt to apply a Western model of democracy; we are witnessing the repercussion of those illegalities today: agitations of various kinds and coups d’état. The numbness inflicted to post-colonial Africa is wearing off and the average citizen is now realizing how their seniors have allowed subjugation and manipulation to be institutionalised. That incapacitation of the post-colonial African state could be achieved through one medium and one medium only: dictating what type of instruction should be allowed in Africa, stripping political thought and critical thinking off their importance, and that could only be done if reading, information, and history are downplayed. The neglect of literature and history in African schools is therefore both a nefarious factor and disheartening consequence. These two subjects have to regain their noble status in the school curriculum if African countries want to truncate the cycle of poverty and instability they are currently wallowing in.

Moussa Traoré is Associate Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.