Rasta, resistance and respectability in modern Britain

The emergence, influence and popularity of the Rastafari religion, ideology or movement in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain was primarily caused by two main interrelated factors. One was the over-policing and criminalization of young Black men in several urban cities and towns such as Bristol, Birmingham, London and Manchester. The second factor, largely in response to this, was a series of organised Black resistance campaigns against such oppression through spiritual soul-searching and a yearning to reconnect physically or emotionality with the African continent. As Ernest Cashmore writes in his book, Rastaman (1980), the origin of Rastafari in Britain was, therefore, born out of the race relations crises in the country during this period. In Aleema Gray’s PhD thesis (2022) “Bun Babylon”, based primarily on interviews of Rastas, the main claim is that Rastafari also incorporates broader issues like anti-colonial resistance, and Pan Africanism, which helped to shape the ideas of this emerging political force in post-war Britain. While the formalisation of Rastafari began in Jamaica in the 1930s primarily as a political and social resistance against British colonial rule and the dominant cultural influence over the country and its people, these broad sentiments were similarly found in Britain. While Rastafari in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain was commonly associated with negativity around Black resistance, ganja smoking and criminal activity, it can be asked whether forty years later such anti-Rasta sentiments are on the wane.

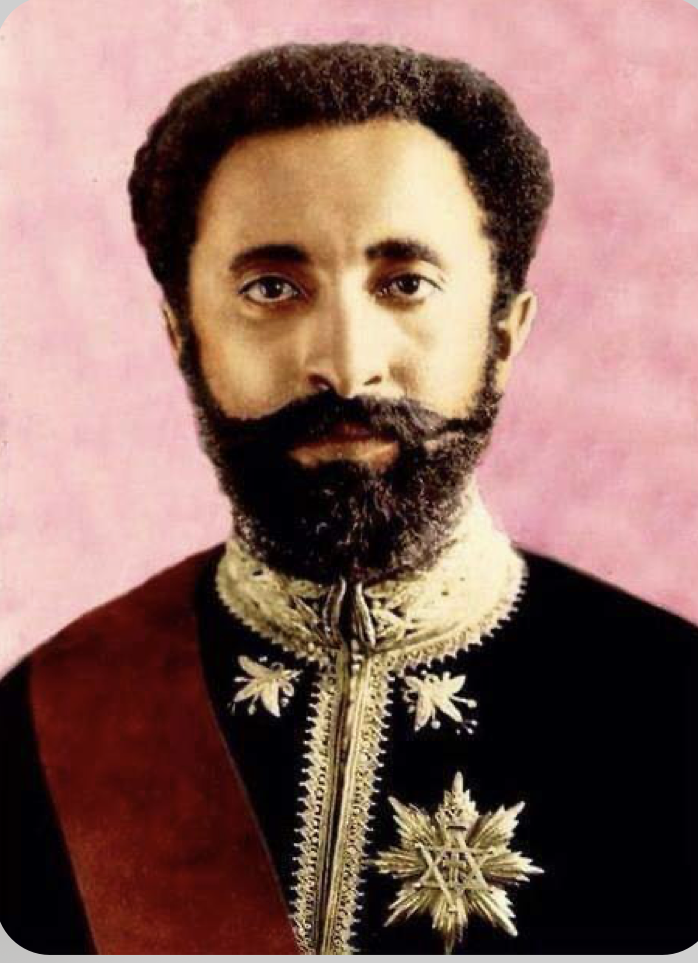

According to the Police Chaplaincy website (strangely, one of the main institutions that have arraigned Black men, particularly Rastas, over the years) there are just over one million adherents of the Rastafari faith worldwide. The 2001 census in the UK found there were 5,000 Rastafarians living in England and Wales. While much of the emphasis on the origin of Rastafari in Britain concentrates on the post war period, in Wimbledon, London, there exists an old bust of His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia, who lived in exile in England from 1936-40. At this time, he was given a great deal of respect by the people of Britain. A few decades later, however, the period was dominated by tensions between Rastas and the wider society. Things have slowly changed for the better in more recent times. For example, the Rastafari Council of Britain sees itself as more than just a religion, but as a way of life, a social movement and a particular mind set. Individuals like Benjamin Zephaniah, the poet and writer and Levi Roots, the businessman and chef are familiar faces on UK TV who have helped to reset much of the national dial.

Apart from these TV celebrities, however, a number of other Black British people have helped to raise awareness of, and respectability for, Rastafari. Captain Kidane Cousland, or Danny, as he is popularly known by his comrades, was the first officer of Rastafarian faith in the commandos. He went on to set up the Defence Rastafari Network to help support other Rastafarians in the military. In 2021, he was awarded an MBE for his work setting up and building the Defence Rastafari Network. Created in 2017, the network supports serving Rastafarians in the military. Figures by the BBC show that in the UK people from ethnic minorities comprise 2.5% of the officers in the armed forces and 8.8% of the people below the rank of officer.

In a report by the newspaper the Voiceonline (March 2022) based on interviews with Rasta women in Britain, one contributor, Sheeba Levi Stewart, a member of the Rastafari Movement UK, told The Voice that the music of a newly independent Jamaica and the moment she first saw His Majesty, was what began her journey as a Rasta. She claimed that post-war London was already emerging as a cultural hub of merging ethnicities and cultures from around the world, and the reggae sounds of Bob Marley, Burning Spear and Israel Vibrations became a daily part of her life. Although it is still not fully understood (or appreciated) by many in Britain, Rastafari men and women can now go about their lives without having to take nervous glances over their shoulders. They are slowly and firmly on the road to gaining greater recognition and respectability than in the 1970s and 1980s.

Dr. Tony Talburt is a senior lecturer at Birmingham City University in the UK.