The hidden truths behind the war in Burkina and Pandora’s song in this context

Some of my previous reflections opened the debate on the role of the armed forces in the war against terrorism in Burkina, Mali and Niger. I am touched upon the power that the songs by the soldiers have on the morale of the combatants. This piece takes a critical look at some of those artistes, people who double as musicians and soldiers, in a country where a ferocious war is being waged against terrorism. The enemies in this conflict are referred to as a terrorists since causing terror is their main goal, a situation which has been evident from the onset of the conflict in 2015 till now.

The men who unleashed terror in Sahelian West Africa were initially referred to as “armed and unidentified men”, since nothing was known about them, except that they carried weapons. Gradually, some information was uncovered like the locations they hailed from, the support they benefitted from (if any) in the countries they targeted. That led to statements such as these terrorists are equipped by external sources (and France was pinpointed) since President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré of Burkina Faso refused to “take in” terrorists whose comfort and security France entrusted him with. Indeed, former Burkinabè president, Blaise Compaoré, accepted such a deal several times. Reliable sources have stated that Compaoré accommodated in Burkina several leaders of terrorist movements. Then, more details contend that negotiations with those terrorists would occur. One of the main emissaries of Compaoré was General Gilbert Diendéré.

With all these facts being exposed, not much extra proof was needed to support the thesis that Paris selected, trained and equipped the leaders of the terrorist movement. This series of instigations on the identity and motive of the terrorists destabilizing the three above-mentioned countries led to another mind-boggling fact. The ousted president of Niger, Mohamed Bazoum, was trained by France until he was ready to lead terrorist operations. Many African universities have Bazoum’s credentials since he was schooled there. Further evidence shows that he was later ordered to ensure and safeguard the interests of France, thus, trampling over the well-being of his own people, that of Africans in general and Sahelian West Africans in particular. This might partly explain the massive support from which General Tchiani benefited when he took power. The populations of Niger saw in the general a “messiah” who had come to establish truth, order and fight betrayal.

Let us hope that the wishes bestowed on the general will keep augmenting and fulfilling the aspirations of those who were dubbed for centuries “the wretched of the earth”. This is not too strong an expression since Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have always been classified as the poorest countries in Africa and in the world. The question one is certainly tempted to ask is the following: why are these three countries, known to be the poorest in Africa, being targeted by terrorist attacks? There is certainly incongruous. Generally, wars are fought over lands that have features or resources that are precious and worth fighting for. The most direct examples are the US and French imperialism: North Americans always send troops to countries that are either strategically situated, or states that abound with natural resources like oil, diamonds and more. Jibuti, Iraq and Libya are examples. Recent research has shown that Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger are very rich in all the mineral resources that Western countries covet. The truth is simple, and it is embedded in this belief and statement: Let us make them believe that they have nothing, both on and under their “their soil” and we will exploit those riches at the right time.

Several studies concluded that no precious minerals were found in Burkina. The paradox is that this country is gradually finding its place among the biggest gold producers. The uranium of Niger which was trivialized and bought at an extremely low prices by France was, in reality, the secret behind the street lights in France. Fallacies of this kind abound. It is, therefore, not a surprise that the terrorists are proving very determined in their fight to destabilize the three nations. Most analysts posit that the aim of the that war is to put or keep pro-West puppets at the head of affairs in these three countries and Western hegemony, precisely France, would carry out a thorough and gluttonous extraction of the minerals. That could, for instance, explain the number of coup attempts Captain Traore of Burkina has survived. Barely a month passes without news of a coup being thwarted.

It is now a cliché to say that the defence of important materials or properties is essential. In this war that is lasting so long, over the most precious resources, each camp pulls out their most reliable, sophisticated armament. Terrorists keep using more and more sophisticated arms, and the armies in the three countries work towards reinforcing the capacity of their armies. In the case of Burkina, what is called “peace effort” (the contribution of citizens and comes in the form of tax when they purchase items) and that patriotic gesture, when added to the moneys in the national coffers enables the country to buy sophisticated top-notch weapons, aircrafts and more, and also recruit and train more soldiers.

Music and resilience

But what should not be ignored in the resistance and resilience of the Burkinabè army is the effect of music. While this has certainly occurred in many conflicts before, I find the case of Burkina worthy of contemplation. Some of the combatants wholeheartedly use their songs to reinvigorate their comrades, to sensitize civilians to support the ideals that the national forces are fighting for and to celebrate the departed ones, the fallen heroes.

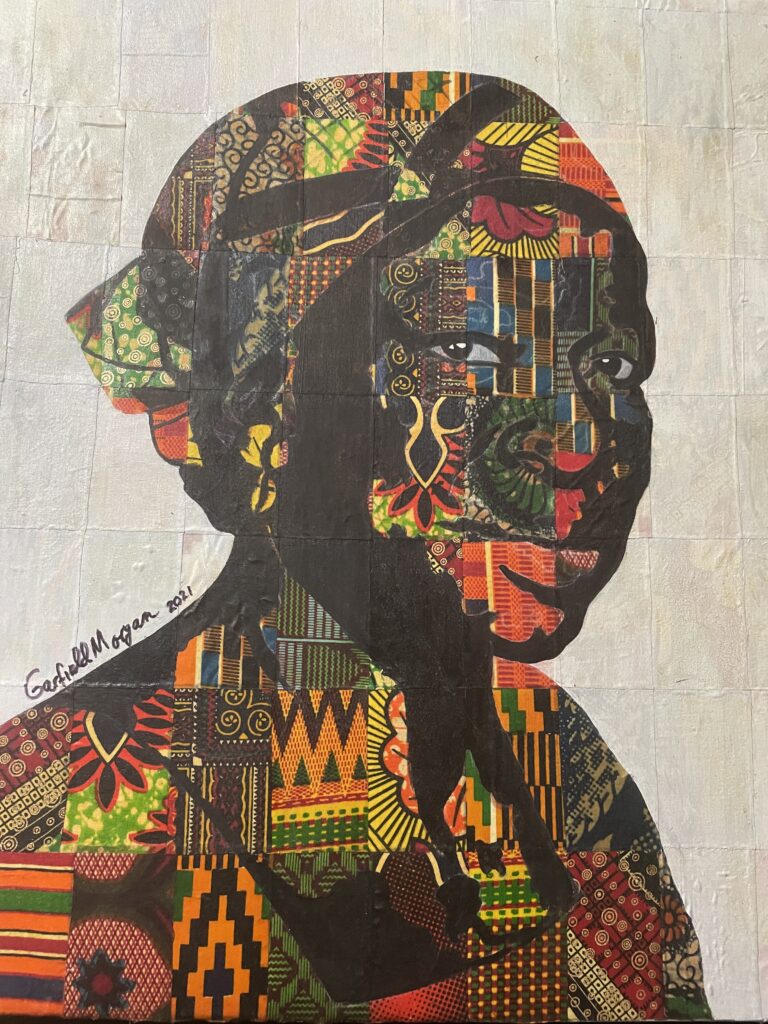

Privat, whose real name is Mardocher Privat Yad Siogo, is a young gendarme (a member of a military and security force in Francophone countries) or pandora. The 19th century French musician Gustave Nadau named the gendarmes “pandores”, pandoras in English. I find the Privat’s work worth looking into, in this context of war. The artiste states that being a military cum singer was his dream and he adds that what motivated him to pursue singing was the effect that his songs had on his co-trainees, before they were sent to the front. His co-trainees encouraged him to have his songs recorded although he thought that these songs were not of the requisite quality. In Burkina, many agree that Privat’s ‘Sodaga’ (soldier in the Mossi language) is a great hit. Released in 2021, that song is a harmonious combination of what should be expected in a context of war, not any kind of war but the type that Burkina Faso is currently fighting: patriots on the battlefield who left everyone and everything behind for the defence of a bigger, national cause, the re-conquest of the national territory, a country which terrorists and their Western allies are bent on snatching. Several analysts perceive the war as an attempt to destabilize Burkina to such an extent that it will lose the characteristics of a sovereign nation state that will make it ripe for the looting and sharing among hegemonic nations.

The lyrics and the videos of ‘Sodaga’ are revered by people from all walks of life. The scenes in the videos are emotional and convey the reality of today’s Burkina Faso. They include a soldier singing in front of his comrades-in-arms demonstrating his pride in being a soldier who brings peace through the use of his weapon. Another scene captures a soldier who is taking a breather, or a little rest and re-creation, during which he gets engaged or married to his girlfriend, before a joyous audience. Minutes after the soldier puts the ring on his girl’s finger, his phone rings and his superior summons him back to duty. The celebration ends and a mood of sadness engulfs the scene as he leaves. Parting is difficult, love, attachment and feelings of melancholy are expressed. His partner is devastated. But, the nation is more important than individual life events. The third chunk of lyrics and images that depict the sense of self-sacrifice feature a combatant who kisses his pregnant wife and daughter, the latter is playing with her friends. The girl is joyous because her dad, the sodaga, is home. Then the time comes for the father/ soldier to say “good bye” and head back to the front. The sadness and pain they face could not be hidden. Leaving one’s pregnant wife, one’s cherished daughter and best friends, not knowing if one will ever see them again is certainly not easy to handle. But the Burkinabè soldiers have chosen that path. Widows, orphans, bereaved friends and family members have become a considerable proportion of the Burkinabè population. But, the sacrifice continues; the anti-terrorist combat goes on with the repossession of the national territory as the goal.

Moussa Traoré is Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.

War is obviously our enemy. Those that war has made them widow and orphans are enormous. But in all a continuous peace is what we wish.

Wow! another wonderful piece that describes the importance of the armed forces in combating terrorism in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, as well as highlighting the geopolitical and socio-economic dimensions of the conflict. I’m saddened how these countries, despite being rich in natural resources, have been destabilized by terrorism, allegedly fueled by external powers with vested interests. This piece has explained the sacrifices of soldiers and citizens alike in their fight for sovereignty and survival, and has also revealed hypothetical relationships between Western hegemony, local leadership, and resource exploitation.

Also, another focus is on the impact of music, especially the work of Privat, a soldier-musician whose song Sodaga describes the resilience and patriotism of Burkinabè soldiers. Through its emotional lyrics and visuals, the song mirrors the sacrifices of soldiers leaving their loved ones to defend the nation, while also celebrating their courage and unity. This piece effectively shows how art, even in war, can inspire hope, galvanize national solidarity, and honor those fighting for a greater cause. In all, you’re indeed a genius. I love the write-up. I’ve developed profound love for Captain Ibrahim Traoré through your write-ups. Take care.