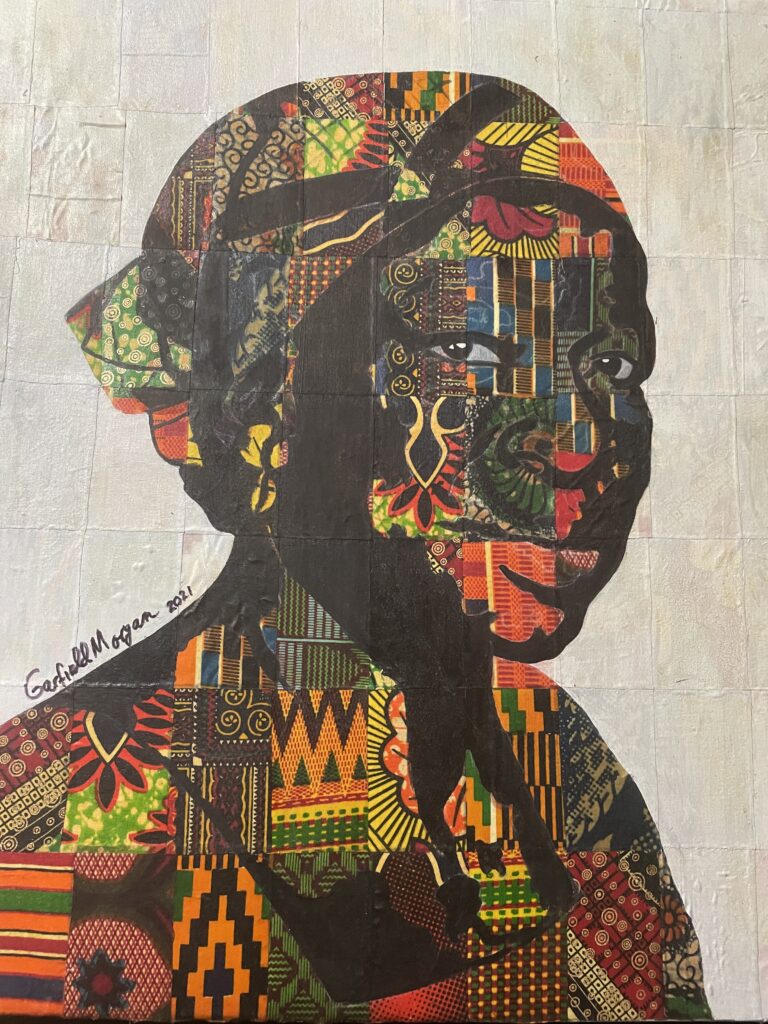

Women and young girls’ health in Ghana

Women’s health remains a global public health concern. It would be a truism to state that the health and wealth of any society largely depend on the health and wealth of its women. Women’s health was emphasized by the Beijing 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also uphold women’s health. Over the years, the Government of Ghana has attempted to improve access to health services through some policies, with the most current one being the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) established in 2003. It has faced hindrances that undermined its reliability: long queues and waiting times, poor quality of medicines, and the negative attitudes of service providers. A close look at women and young girls’ health in the Central Region of Ghana reveals very important information that cannot leave us indifferent. Strangely enough, several factors contribute to nullify the sanctity of human life, especially that of women, teenage girls and children.

Common heart-wrenching scenes

Ghana is generally known as a country that has made considerable efforts in the health care sector. Health care-wise, Ghana is ahead of many countries in the sub-region, to such an extent that many patients who suffer from certain diseases and conditions are told to explore the “Ghana side”. That image got boosted when cardiothoracic surgeon, Professor Frimpong-Boateng, returned from Germany and performed open heart surgery in 1992. The alliance that has been encouraged and established very early between orthodox medicine and herbal medicine also contributed to make health care more performant in Ghana. In the midst of this pleasant tableau of progress, security and satisfaction, one often runs into horrendous cases where people battle between life and death, in circumstances that are paradoxical, and incongruous. Data shows that the central region of Ghana (Capital, Cape Coast) is among the poorest regions of the country, despite the abundance of natural resources. The sea, minerals, forest and others co-exist with need and want, residents whose main habit is soliciting help from everyone who is not from the region or not from Ghana. Cape Coast is a tourist town, and the general belief is that residents who hail from other areas are rich, they are taken for tourists most of the time. That leads to boys and girls, young men, women and adult women soliciting money from people. ‘kyem sika’ ( please give me money) seems to be the mantra for many residents. Youngsters, women and girls face the harshest of the consequences. They contract STDs, HIV/AIDS and unplanned pregnancy. A climate of promiscuity is, therefore, automatically created and sex becomes the central component: teenage pregnancy is rampant (10,301cases in 2021), HIV/ AIDS infection is among the highest (24,881 cases in 2020). That reality affects the coastal zone in general – from Accra to Winneba, Cape Coast, Takoradi, and Sekondi, the flail is present because the same habits exist. A colleague of mine witnessed a scene some few weeks ago and strongly encouraged me to feature it. At Mankessim Roundabout (38 km from Cape Coast) a heavily pregnant woman was being conveyed on a tricycle to a healthcare facility for delivery. It took the benevolence of the passengers on a minibus that happened to be journeying on that way to transport the woman to the healthcare center.

General politicization and little check

This incongruity stems from the politicization of almost everything. During its 2016 campaign, the party in power promised, among others, an ambulance for every constituency. Evidence attests to the fact that the ambulances have been purchased and distributed to the constituencies. While ambulances are fueled by the government, the drivers and health practitioners on the ambulances charge the relatives of the patient a minimum of 400 Ghana Cedis (about 67 USD) which they pocket. The “general politicization” is disastrous. Useful and accurate reports sent to the ministries from NGOs on the terrain are brushed aside. Such scenarios and many others lead citizens to contend that healthcare is not a genuine priority for the political authorities. Women, pregnant teenagers (14-20 years) and boys are those who suffer the most, since they need and seek more medical attention. Cases of abortion are too frequent, carried out in dangerous conditions and put teenagers’ lives at risk. This complicates the health condition of young girls. They become young mothers who descend into an “inferno”. The fathers are equally young and penniless in most cases; adult fathers refuse their responsibilities, since they parted with money in the affair.

The above-mentioned woman is a resident of a village around Mankessim, where there is a polyclinic and the conditions in that polyclinic might have led to making the dangerous trip to a bigger town for safe delivery. There is, probably, a quasi-inexistence of medication, equipment and personnel. Many nurses and doctors posted to rural areas work to change their posting, to work in a more comfortable area, a real contrast in the medical field. A visit in a ward in many dispensaries in today’s Ghana shows patients lying on the floor because of the low number of beds; bicycles and motorbikes replace ambulances. Many conscientious citizens find this to be unacceptable in the twenty-first century.

Possible solutions

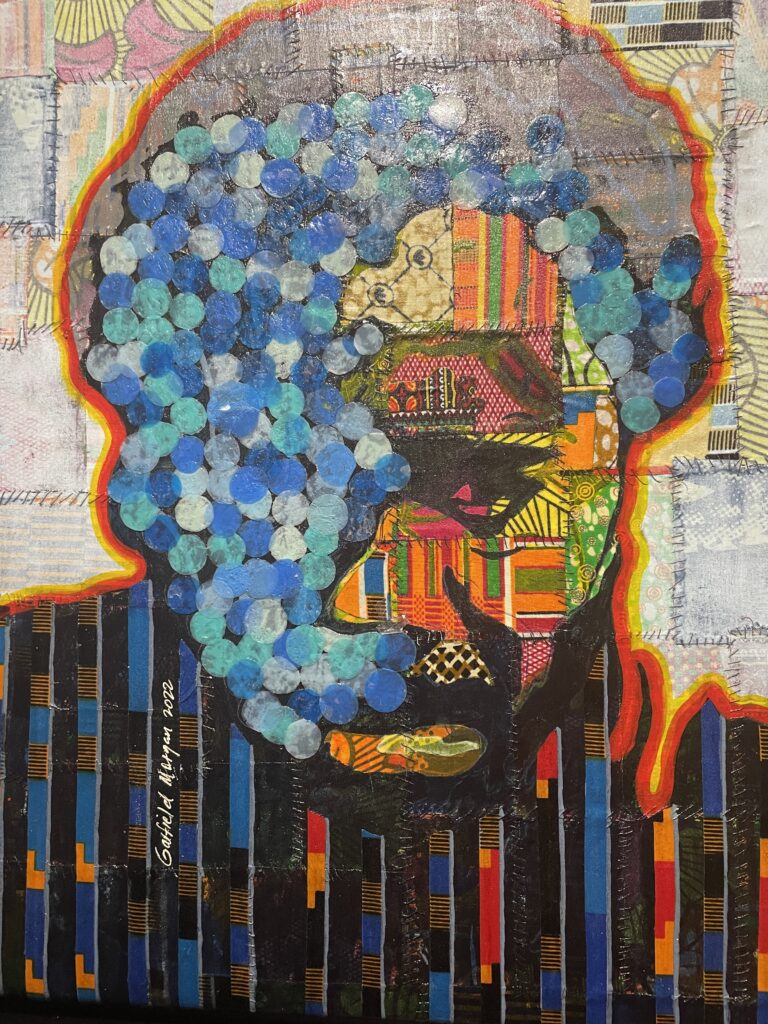

A reinforcement of research in herbal medicine and its application could salvage many lives. It is efficient therapy and affordable since it is cheaper than hospital treatment. People tend to trust herbal medicine more, they see it as something that is closer to them, produced by them. Encouraging a robust collaboration between specialists in herbal medicine and orthodox or western medicine would improve the lot of patients, especially women and female teenagers. The medical profession is one that is founded on devotion, passion and calling. Nurses and doctors need to put aside the search for comfort and prioritize the treatment of patients. A bare minimum of comfort is made available to all health workers across Ghana so reversing posting does not have any solid justification. Students from the most deprived areas, like northern Ghana, choose to enroll in medical school at Korle-Bu in Accra and decide to practise in the southern part of the country after their training. As a result, the dearth of physicians is a reality in northern Ghana. Training northern medical students in the medical school of the north (at the University for Development Studies) could mitigate the problem. Trainees from deprived areas could sign a bond that makes it compulsory for them to return to serve in their communities. The Cuban medical brigades that gallantly used to work in any part of Ghana and under any condition(s) were expelled from the country some few years ago. That left many rural areas with no health workers and people were left to die. Keeping children and adolescents in school on professional programmes could help. The training of health practitioners has to be reconsidered. Selflessness and the sense of duty must be repositioned at the centre of healthcare. The teaching of sex education must be re-examined. It has failed the people.

Moussa Traoré is Associate Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.