Painting the city – Part 1

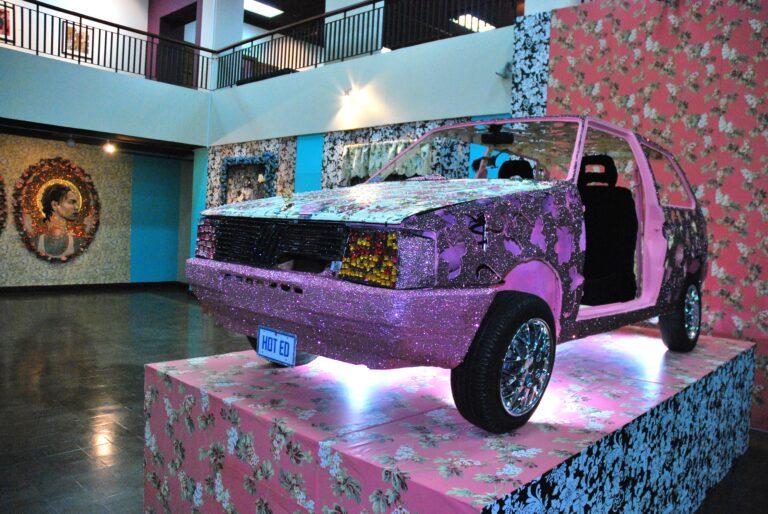

Hardly a week goes by, these days, without a public relations (PR) announcement about a new mural project in downtown Kingston. It is hard to keep track of the numbers but in recent times, more than 60 new murals have gone up, piloted by organizations such as Kingston Creative and the Kingston Municipal Corporation. The mural campaign, which has been branded as Paint the City, is framed as part of efforts towards general urban renewal and the establishment of a Downtown Art District. Many are sponsored by corporations and other organizations that operate in downtown Kingston and some have been commissioned for the walls of their headquarters. There is a specific initiative to “muralize” Water Lane, part of which has already been pedestrianized, and to create a walkable connection between the Institute of Jamaica on East Street and the National Gallery of Jamaica on Orange Street. The Duke Street Museum project is another initiative in the area and involves mural and other public art commissions.

The mural campaign

The mural campaign is, as such, a laudable initiative that brings beauty and cultural interest to the areas in question. The establishment of a focused Downtown Kingston Art District should greatly benefit the Jamaican cultural sector – with “art district” conventionally meaning a recognized area with a high concentration of cultural activity and enterprise, such as museums and other cultural institutions, commercial and non-profit galleries and performing arts spaces, studios and rehearsal spaces, craft markets and design stores, public art, historical sites, and a variety of cultural events. Critical questions, however, arise that need more than a glib PR response if these initiatives are to be as socially and culturally beneficial as they should be.

One key question is what intervention these projects really make into the social and cultural environment of downtown Kingston, beyond the obvious beautification. Downtown Kingston is often described as primarily a business district, but it is also a residential area, where some 80,000 people live, most of them in the lower income category, and where people of all socio-economic backgrounds work in formal and informal jobs. It is complex, contested terrain with a history of social tension and conflict – socially, politically, and in terms of how the communities within position themselves towards each other, with criminal gang activity as a factor to be reckoned with. It is also a part of Jamaica whereby highly developed and cared for modern and historical infrastructure coexists with deep neglect and facilities which are barely suitable for human habitation.

Another media outlet recently carried an article with a photo of a broadly smiling female vendor in front of a mural, assured us that the residents do appreciate the murals, which I am sure most do. But the article, inadvertently, also drove home that the mural campaign does not emanate from within the community but is largely the work of “uptown” organizers and couched in notions of benevolent patronage.

The mural campaign has already been criticized for amounting to a colourful “band-aid” applied to Downtown’s urban blight, without being supported by substantive action regarding the underlying and pressing social and infrastructural issues. At the time of writing, a state of emergency is being considered for Central Kingston, because of the worrisome increase in crime and violence in the area, recently. A mural campaign or an art district will do nothing to stop such developments, unless it is couched in thoughtful, comprehensive community action.

Art districts

Art Districts have a bad reputation in the critiques of urban development and their appearance is often linked with gentrification – a problematic social effect of urban renewal, which may or may not be deliberate, whereby property prices go up and social dynamics change in a way that marginalizes and displaces the original residents. There is a saying that “the artists come first, and the developers follow.” In many parts of the world, artists have recognized this problem and taken a position against unchecked gentrification, by becoming community advocates and activists who use their public visual voices and other creative interventions to agitate for inclusive social change. While the current mural campaigners in downtown Kingston insist that they consult with the communities and use community artists in some of the projects, there is only limited evidence of any such commitment and, if the PR is anything to go by, many of the murals seem to serve corporate rather than community interests. Claiming to be committed to “balanced, inclusive development,” to use the euphemism of the day, amounts to mere lip service and, as such, achieves nothing at the social level.

Next week we will look at some of the new mural projects and their significance, in comparison to more traditional street art in Downtown Kingston.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She lectures at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica, and works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant.