Memoir: Meeting Mr. Tabois

I vividly remember my first encounter with Gaston Tabois (1924-2012), at least in terms of the impression he made on me rather than for the occasion itself. It must have been in late 1984 or early 1985, when I had just started working in the National Gallery of Jamaica’s Education Department, and the occasion was a function, probably an exhibition opening. A grey-haired, dapper-looking gentleman in a sharp dark suit arrived early and shook hands with all the persons he encountered, myself included. He was very formal, and I initially assumed that he was a government official, or perhaps a pastor. It turned out that he was the self-taught artist Gaston Tabois, one of the artists the National Gallery had labelled and consecrated as an Intuitive. His appearance, and formality, defied the preconceptions we often have about artists and, even more so, about self-taught or Intuitive artists. His unique story, in fact, provides us with a good opportunity to reflect on some of those issues.

Gaston Lascelles Tabois was born in Trout Hall, Clarendon, and grew up in Rock River, near Chapelton, where he attended elementary school. His sense of discipline and commitment to lifelong learning was, he later recounted, bestowed on him by his mother, who was actively involved in his early education. Tabois later attended the College of Arts, Science and Technology (now UTech) and also Dillard University, a historically Black university in New Orleans. He worked as a civil servant in the Public Works Department, where he acted as chief draughtsman before turning to art full-time. His wife was a teacher, and the family was part of the emerging Black Jamaican middle class around the time of independence. His daughter, Alison Tabois is a graduate of the Academy Drama School in London. Alison is perhaps best known for her work as the co-creator, writer, producer and voice director of The Cabbie Chronicles, a series of short animations that was streamed on Flow TV.

Tabois’ first solo exhibition was in 1955 at the Hills Gallery on Harbour Street, Jamaica’s first major commercial gallery, where he exhibited his paintings and drawings regularly after that. The following year, he was included in an exhibition of Jamaican art at the Barbizon Hotel in New York City, which was organized by the Hills and sponsored by CBS president and MoMA trustee William S. Paley. In 1956, Tabois also exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas. Tabois was, along with Kapo, one of the self-taught artists who were being promoted locally and internationally by the Hills Gallery as Jamaica’s answer to the international success of the “Haitian Primitives.” While the Hills also sought to engage and cultivate local audiences and buyers, tourists were an important part of their clientele, and this included the international celebrities who vacationed in Jamaica at that time. Elizabeth Taylor and her then husband Eddie Fisher bought three of Tabois’ early paintings.

Many early works by Tabois thus left the island and may not be recognized by their current owners as Jamaican artworks of significance. Some 25 years ago, a colleague in New York City, who is familiar with his work, bought an early Gaston Tabois painting at a flea market on Washington Square for just a few dollars, and had it professionally restored, as there was a tear in the canvas. The work still had the Hills Gallery label on the back and is stylistically related to his Reaping Sugar (c1955) in the National Gallery of Jamaica’s collection.

Tabois’ early works comfortably fit the expectations the public had of self-taught artists from the Caribbean, in terms of its formal qualities and subject matter. If Kapo’s work spoke to the spiritual side of self-taught art in Jamaica, related to his role as a leader in Revivalism, Tabois represented its realist side. He mainly painted the world he was familiar with, such as country scenes with road and sugar workers, vernacular buildings, and popular cultural traditions such as Jonkonnu, with a meticulous, almost obsessive attention to detail that betrays his technical draughtsman’s eye.

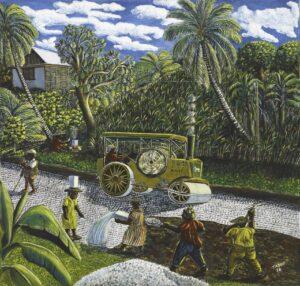

These characteristics are perfectly illustrated by Road Menders (1956) in the National Gallery of Jamaica collection. The painting depicts a road paving scene, with men and women doing manual work laying down the marl, while another worker is operating a mechanized road roller, marked P.W.D. (Tabois’ place of work). The scene is set in a rural environment, with a variety of farm crops growing in the fields that adjoin the road. Every detail gets equal attention: the wattle-and-daub wall of the building on the upper left; the textures and patterns of the crops, trees and other plants; the clothing and actions of workers; the various construction activities and tools and materials used; the heavy machinery; and, more subtly, even a utility pole and line.

As is commonly seen in self-taught art, there is a strong tension between the two- and three-dimensionality of the composition and this adds a surreal quality to the image. Several strong, intersecting diagonals (mainly the strong light-coloured band of the road itself but also the boundary of cane-field and the trees that tilt in opposing direction) suggest depth but also form an intricate flat design that is reinforced by the patterns and textures of the plants and structures. This spatial ambivalence is perhaps most extreme in the roller, which seems to lift up partially from the road, while we are not sure whether we are looking at the outside or inside of its mechanisms, as it appears that we are seeing both.

With the dry wit that is typical for his work, Tabois also pays attention to the practicalities of a work site: with the sun high above, it will soon be time for lunch and a lady is already busy cooking the food on an open fire on the side of the road, as is indeed common practice at work sites in Jamaica. And, of course, there has to be an idler: the distracted, mango-eating figure to the left, although he (or she) may be a passer-by or a child. Overall, the painting presents a scene of Jamaican life which is still familiar today, but it is also a fragile, disappearing world, in which the traditional is already being replaced by modernity, which is represented by the heavy machinery in the centre of the scene; the utility pole and line; and, by implication, the cars and trucks that will soon drive on the newly paved road.

The world depicted in Road Menders, and other such paintings by Tabois, is one which is at the same time momentary and curiously solidified, which adds to the scene’s surreal quality and alludes to submerged meanings beyond its cheerful, documentary impulse. David Boxer masterfully interpreted these tensions in his introduction to the Fifteen Intuitives (1987) exhibition catalogue: “It is this wistful nostalgia, a gentle railing against the passage of time that I feel is behind much of the subconscious, intuitive drives of Tabois’ art… It is an obsession, I feel, a deep-rooted desire to make the impermanent permanent: to banish time, decay and death. Consequently, the most fleeting elements in a painting become frozen into unyielding shapes. Clouds are carefully patterned; great attention is paid to shadows, and reflections in glass or water become heavy, solid and ‘real’. Expressions of transitoriness abound: smoke being exhaled from a smoker’s lips; fluttering curtains; fleeting glances and shifting smiles – memento mori all”. From that perspective, there is nothing “naïve” about Gaston Tabois’ paintings.

In the concluding part of this column, next week, we will take a closer look at the further development Tabois’ work and the critical response it has received.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. The second, revised and expanded edition of her best-known book “Caribbean Art” was recently published in the World of Art series of Thames and Hudson. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.