Travel Report: Reframing Haitian Art at the Tampa Museum of Art

I recently had the opportunity to visit the Tampa Museum of Art for the Reframing Haitian Art symposium, held there on June 9. The symposium brought together some of the key promotors, conservators and researchers of Haitian art. It was held to accompany the Reframing Haitian Art: Masterworks from the Arthur Albrecht Collection exhibition which closes on June 23.

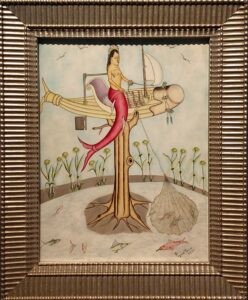

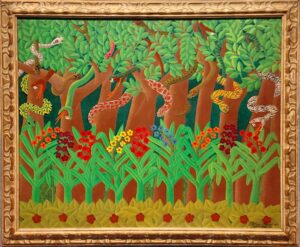

The exhibition was selected from a donation of some eighty works by various self-taught Haitian artists, including “big names” such as Rigaud Benoit, Wilson Bigaud, Préfète Duffaut, André Normil, Philomé Obin, André Pierre, and Salnave Philippe-Auguste, all made from the 1960s to the 1980s. Most of these artists were associated with Le Centre d’Art, an art centre and school in Port-au-Prince which has been instrumental in shaping the direction of Haitian art since the mid-20th century and celebrates its 80th anniversary this year (about which I will write more soon). The Reframing Haitian Artexhibition was guest-curated by Edouard Duval-Carrié, a Haitian artist and curator based in Miami. The late Albert Albrecht, a San Francisco lawyer, was an avid collector of self-taught Haitian art and his collection has now found a permanent home at the Tampa Museum of Art. The donation also included historical documents, such as maps and prints, of which we also got to see examples during the symposium, along with a few artworks that were not in the exhibition.

Any collection or exhibition which focuses exclusively on self-taught, popular Haitian art inevitably presents a one-sided view of Haitian art, as academically trained artists have also practised in the country. From the 1940s onwards, and largely through the interventions of Le Centre d’Art, the self-taught artists almost immediately outshone their academically trained counterparts, in terms of the vitality and originality of the work produced as well as the international critical acclaim and market support they received. This, inevitably, became a source of tension in the Haitian art world. Some saw the promotion of self-taught, popular art as an unwelcome genuflection to the primitivist preconceptions about Black Haitian art, while others lamented the displacement of the mainstream artists from their expected apex position in the Haitian art world. It has not helped that most of the patronage of this art has come from White, Euro-American curators, writers and collectors.

These critiques are legitimate but, as Edouard Duval-Carrie argues, what happened at Le Centre d’Art in the 1940s was revolutionary, as it deeply challenged Haiti’s cultural hierarchies, which were underpinned by deep class divisions, and generated an unprecedented explosion of popular creativity, which went far beyond the more traditional expressions such as the sacred arts of Vodou. As the work in the Reframing Haitian Art exhibition amply illustrates, the results were extraordinary, culturally and artistically, and put Haiti on the international artistic map, although some of the themes and styles that emerged were subsequently watered down in highly repetitive, commercially oriented emulations. There is no doubt, however, that it is Haiti’s self-taught, popular art, in its original forms, that is most unique and distinctive about Haitian art, far more than what has been typically produced and supported by Haiti’s social elite. Recognizing this, and challenging the corrective narratives that have sought to downplay the importance and validity of this kind of art, is part of Duval-Carrie’s curatorial agenda in Reframing Haitian Art.

One of the challenges with curating such Haitian art for an American museum context is that such artworks were not created for the standard “white cube” interior architecture. This inevitable tension between cultural contexts was, however, quite effectively addressed in the exhibition design. The exhibition walls are painted in an intense blue, that alludes to the sea and the heavens and creates an immersive environment that resonates with the imagery in the paintings. The irregular hanging, with works mounted at different heights, pointedly departs from the conventional, static method of hanging works of art along an established “sight line.” This irregular mounting presents a more dynamic experience, with competing viewpoints, and demands more active, engaged viewing, while also gesturing at the more organic, cumulative methods of display in Haitian popular culture, for instance in the markets.

The Tampa Museum of Art is one of several museums in Florida that have been in the foreground of exhibiting and collecting Caribbean art in recent decades. In many ways this has occurred naturally, because southern Florida is, culturally and geographically part of the Caribbean, with large and influential populations of Caribbean descent, but it has also involved clear efforts to give prominence and visibility to art forms and artists that were previously underrepresented in American contexts. At the Tampa Museum of Art. this Caribbean focus is largely the work of the curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Joanna Robotham, who has family connections to the Caribbean (her husband is Jamaican), with a consistent exhibition focus and major acquisitions, including several major donations, of which the Albrecht Collection is one.

During my visit, several other exhibitions relevant to the Caribbean were on view. This included Goodbye My Love and a permanent exhibit, Hybrid of a Chrysler (2016), a winged vintage Chrysler car, by the Cuban artists Esterio Segura and Purvis Young: Redux, a stunning installation by the late, Miami-based self-taught artist Purvis Young, who was of Bahamian descent, selected from a large donation to the museum by the Rubell Family Foundation. There was also an exhibition of Haitian Vodou flags, or Drapos, consisting of donations from the Ed and Ann Gessen Collection (whose home and collection of Haitian art we were also able to visit, as part of the symposium programme). Other Caribbean-linked exhibitions are being planned and I am sure that this will soon also include Jamaica. My only beef about the current spate of exhibitions and acquisitions by American museums is that very little of this ever makes it back to the Caribbean, an imbalance that should receive more attention, as there is a growing disconnect with what is available and debated locally.

The Arthur Albrecht collection, which included artworks with serious condition issues, was conserved with a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project by ArtCare Conservation, a private conservation lab based in Miami, Los Angeles and New York City. One of the sessions at the symposium was, in fact, dedicated to conservation, with fascinating presentations on the conservation of the Albert Albrecht collection and on the conservation of three murals that were salvaged from the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Port-au-Prince, which collapsed during the 2010 earthquake and was subsequently demolished. The salvaged and stabilized murals are now in storage in Haiti, awaiting the planned reconstruction of the Holy Trinity Cathedral. The world-famous Holy Trinity Cathedral murals, which were executed by Haitian artists such as Philomé Obin, Castera Bazile, Rigaud Benoit, Wilson Bigaud, and Préfète Dufaut, or some of the same artists who are represented in the Albrecht collection, was a major project of the Centre d’Art that was executed in 1950-51, with some later additions that included sculptural reliefs by Jasmin Joseph.

I was inevitably reminded of the acute art conservation needs that exist throughout the Caribbean, because of the unforgiving tropical climate, natural and manmade disasters, as well as the ad hoc, unconventional art materials used by many artists in the Caribbean, such as Masonite and house paints, which make artworks more vulnerable to decay. Presently, art conservation facilities of any substance only exist in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, with well-equipped and -staffed labs that operate in Cuba and Puerto Rico. Elsewhere in the Caribbean, only basic facilities exist, with just a handful of qualified professionals (and a few self-taught or informally trained conservators who sometimes do more damage than good). It is a situation which needs urgent attention, as there is an enormous amount of conservation work to be done, with many important parts of the region’s artistic heritage already lost or in imminent danger. While this needs to be addressed with a greater sense of urgency on an institutional level, there is also scope for entrepreneurial approaches, in the form of private labs or public-private partnerships, that offer conservation work for private, corporate, and public collections. These are aspects of the cultural and creative industries that have received little or no attention to date in the Caribbean but have great business potential, while addressing significant and consequential needs.

The Reframing Haitian Art symposium was funded by the Kent Family Charitable Fund. Its principal, Larry Kent, is a California-based art collector whose holdings include Haitian and Jamaican art. Kent is an active member of the Haitian Art Society, a US-based members organization that promotes and advocates for Haitian art. Its membership consists mainly of specialized collectors, art dealers, academics, artists, and other art professionals who are engaged with Haitian art, most of them based in the USA and Haiti. The Haitian Art Society’s very useful website (Welcome to the Haitian Art Society – Welcome to the Haitian Art Society) features practically every Haitian artist, listed in a searchable and lavishly illustrated database, and also features collections, publications and news items relevant to Haitian art. It is a major research and promotional tool for Haitian art, which surely contributes to the growing international awareness of the country’s art. It would be a major game-changer to have such a comprehensive online resource for Jamaican art

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. The second, revised and expanded edition of her best-known book “Caribbean Art” was recently published in the World of Art series of Thames and Hudson. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.