The National Gallery of Jamaica at 50: Part 2: Articulating a Jamaican art history

In the first part of this series, we looked at the antecedents and beginnings of the National Gallery of Jamaica (NGJ), which observes its 50th anniversary this year. In this second part, we look at some of the exhibitions that defined those early years. The period was characterized by a remarkable level of activity and a clear strategic focus, with the sort of energetic, inspired sense of mission and direction that would surely benefit the National Gallery today. There were ambitious development plans, and I have seen architectural designs, from around 1978, for a purpose-designed modern wing, which would have expanded the gallery facilities significantly (then located at Devon House), in what is now the overflow parking lot at the back of the property. At an appropriate time the National Gallery was to remove from the historic building. Given the central location, accessibility and popularity of Devon House, it is perhaps unfortunate that the National Gallery was not allowed to stay at that location.

A cohesive art history

The articulation of a cohesive history of art in Jamaica was a prime objective of the early National Gallery. There had been only a few such efforts before. One was the dancer and choreographer Ivy Baxter’s book The Arts of an Island(1970). But, that book was primarily about the performing arts, with only a brief chapter on the visual arts. There was not, as yet, a well-contextualized and well-analyzed history of the visual arts that presented a long-term developmental view. That is the task that David Boxer took on when he joined the National Gallery in 1975 as director/curator and he quickly became the main published expert on the subject. This involved developing a representative permanent collection and an exhibition programme that researched and interpreted that art history, and articulated its foundations in the accompanying catalogue publications, which are important documents, even though they were modestly produced and had limited circulation.

The National Gallery Bulletin, a one-time 1976 publication for a major National Gallery fundraiser, has an instructive essay by David Boxer, in which he presents a thoughtful analysis of the main gaps in the modern collection, and identified works of art that needed to be acquired to tell the story of Jamaican art more effectively, while appealing to the generosity of donors to make this possible. Several of the listed works were subsequently acquired, including Edna Manley’s Beadseller (1922), her earliest Jamaican sculpture; Barrington Watson’s Mother and Child (1958), which is now one of the most popular works in the collection; and Gloria Escoffery’s triptych The Gateway (1965).

David Boxer had already collaborated with Vera Hyatt on two NGJ exhibitions in 1975, initially on a freelance basis, before he formally joined the staff as Director/Curator at the end of that year. One was the Carl Abrahams Retrospective, the National Gallery’s first curated exhibition, and the other was Ten Jamaican Sculptors, which was also shown at the Commonwealth Institute in London. Once Boxer was on board, the pace of exhibitions picked up significantly. Vera Hyatt continued to contribute to the curation of exhibitions until she migrated to the USA in 1980, although Boxer quickly became the dominant curatorial and art-historical voice.

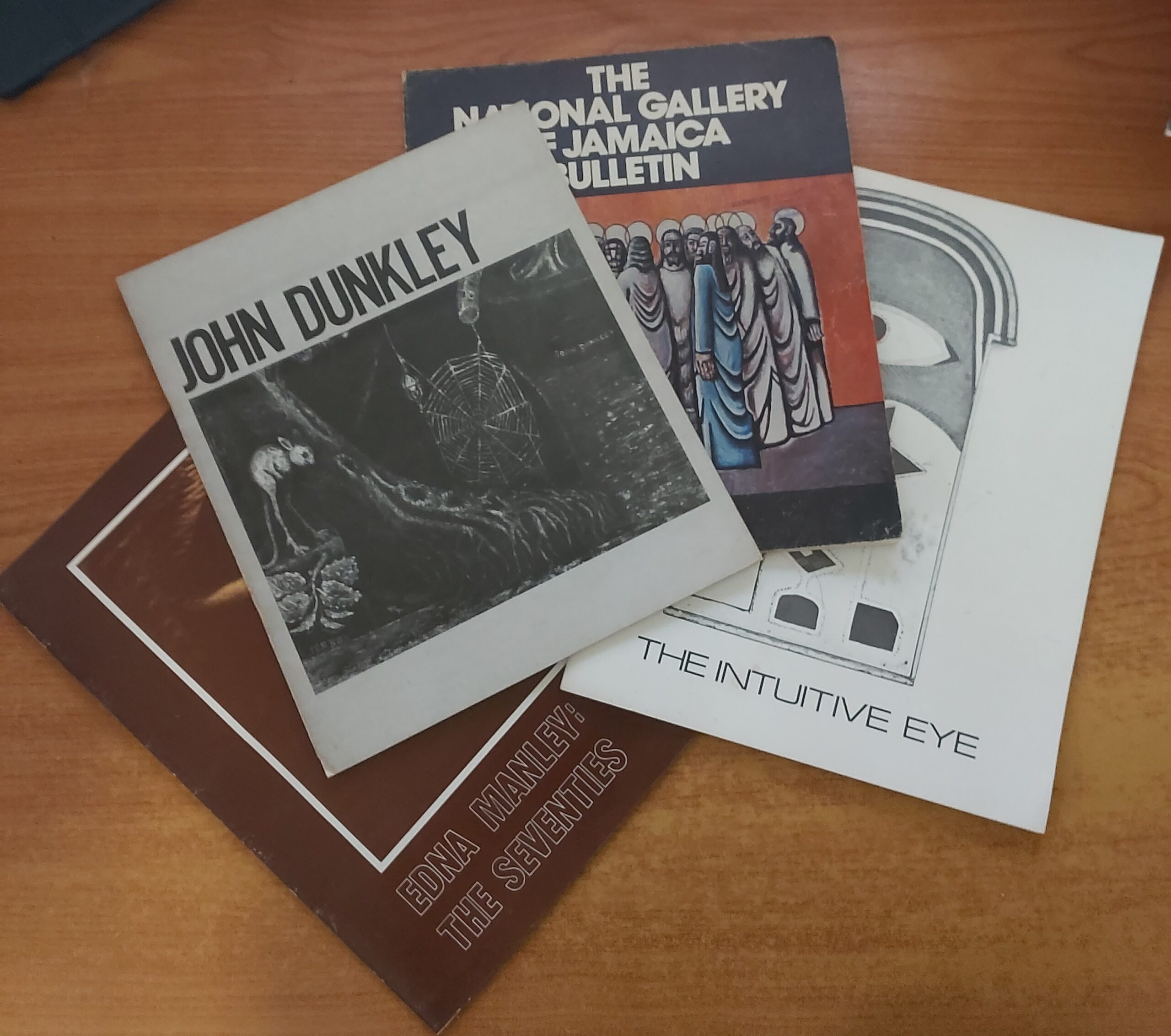

Remarkably, six retrospectives were held between 1974 and 1982, when the National Gallery left Devon House for its present location: for Karl Parboosingh (1975), John Dunkley (1976), Sidney McLaren (1978), Albert Huie (1979) and Cecil Baugh (1981), respectively, in addition to the earlier mentioned Carl Abrahams Retrospective. There were also two partial retrospectives of Edna Manley’s work, namely: Edna Manley: Selected Sculpture and Drawings (1977), which was shown at the Mutual Life Gallery, and Edna Manley: The Seventies (1980), which was held at the National Gallery for her eightieth birthday. These early retrospectives, alone, give us a good sense of which artists mattered most, at least in Boxer’s eyes, and represent some of the pillars of the national canon that was being articulated.

Mandate to exhibit and collect Jamaican art

The 1974 articles of association of the NGJ had specifically mandated the institution to exhibit and collect the Jamaican art that came out of the nationalist uprising of 1938, the date which had been identified in the nationalist historiography as the official beginning of the Jamaican independence movement. This definition posed several problems: it failed to provide modern Jamaican art with any indigenous historical groundedness; it did not accommodate any art that was not nationalist; and, in a specific problem for those who wished to place Edna Manley at the centre of Jamaican art history, it did not account for the fact that her most groundbreaking and compelling works, such as Negro Aroused (1935), were created before 1938. The original transfer of works of art from the Institute of Jamaica, or the foundational collection of the National Gallery, consisted almost entirely of paintings, and a smaller number of sculptures – a narrow conception of “fine art” which did not accommodate art in other media.

These narrow definitions were almost immediately challenged by Boxer in his first major exhibition Five Centuries of Art in Jamaica (1976), which was also the National Gallery’s first survey exhibition. In this exhibition, Boxer added colonial art to the narrative of Jamaican art, starting with the Seville Carvings. As he explained in the catalogue introduction, he had originally intended to include the pre-Columbian era but was unable to do so because of the lack of significant artifacts in Jamaican collections at that time. One year earlier, in the Ten Jamaican Sculptors catalogue, Boxer had argued that Jamaican art history “would hardly begin with the first Jamaicans, the Arawaks [as the Taino were then known], for they contributed little to the Jamaica we know today”. By the time of Five Centuries, he was, at least in principle, willing to incorporate the first Jamaicans into a longer, developmental view of Jamaican art history. Five Centuries was also not limited to “fine art” in its narrow sense and included nineteenth century photography, ceramic pieces by Cecil Baugh, and Art Deco furniture by the designer Burnett Webster (who was from the Cayman Islands but based in Jamaica).

The formative years

The Formative Years: Art in Jamaica 1922-1940 (1978) exhibition was the first National Gallery exhibition in which the year 1922 was used as the starting date of modern Jamaican art, although no justification was provided for the choice of this date, except for that the three earliest works in the exhibition – Edna Manley’s Beadseller, Wisdom, and Ape were from 1922. By documenting the nationalist, modernist work that was produced between 1922 and 1940 by Edna Manley, Alvin Marriott, Albert Huie, Carl Abrahams, Burnett Webster, the photographers Dennis Gick and Roger Mais, and the painter Koren der Harootian (an Armenian refugee who was influential as an art teacher in the late 1930s), the exhibition and catalogue effectively diffused the previous focus on 1938 as the start date of modern Jamaican art while again also going beyond painting and sculpture.

In his catalogue for The Formative Years, Boxer also refined his position on pre-twentieth century art, which he more explicitly subordinated to modern Jamaican art. While he acknowledges the contribution of colonial artists “to an interesting and even significant history of art”, he adds that: “There is no painter, there is no sculptor from this period we can point to and say: ‘This is a Jamaican artist; this is someone painting Jamaica and her people through Jamaican eyes’. Indeed, the true Jamaican artist is a product of the 20th century.”

The Formative Years also included work by John Dunkley and David Miller Sr and Jr, three self-taught artists, which required some chronological gymnastics with the estimated dates for undated works, since these artists had produced few significant and dated works before 1940, but Boxer was clearly determined, from early on, to include them in the emerging national canon. Although this was not elaborated on, he also used the term Intuitive for the first time to describe these artists in the catalogue.

One last crucial addition to the National Gallery’s emerging narrative came in 1979, with the Intuitive Eye exhibition, which gave respectability to the work of the self-taught popular artists by assertively naming them “Intuitives,” rather than “Primitive” or “Naive”, and by attributing to their work the cultural authenticity and legitimacy for which the entire Jamaican art movement had been searching (and which some critics, to this day, claim it is lacking). Key to this claim is the notion that these intuitive artists have evolved independent from Western cultural norms, or as Boxer wrote in the catalogue: “These artists paint, or sculpt, intuitively. They are not guided by fashion. Their vision is pure and sincere, untarnished by art theories and philosophies, principles and movements”.

With these three foundational exhibitions, David Boxer articulated the key elements of a nationalist historical art narrative that was fully articulated in the Jamaican Art 1922-1982 touring exhibition, which was shown in the USA, Canada, Haiti and Jamaica between 1983 and 1986, and the National Gallery’s first, like-named permanent exhibition, which was installed after the National Gallery moved to the Kingston Waterfront in late 1982. The two pillars of this narrative were the centrality of Edna Manley and the Intuitives. Given the politically charged environment in which Jamaica’s art history was being articulated, during the politically turbulent 1970s, and emerging artistic and personal rivalries which were already evident in the Jamaican art world in the 1960s, it was inevitable that this narrative, and Boxer’s power to articulate and communicate it would be challenged. As we will see in part three of this series, Jamaican Art 1922-1982 became the trigger for what became a full-fledged culture war in the 1980s.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. The second, revised and expanded edition of her best-known book “Caribbean Art” was recently published in the World of Art series of Thames and Hudson. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.

![Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and Augustus Charles Pugin (1762–1832) (after) John Bluck (fl. 1791–1819), Joseph Constantine Stadler (fl. 1780–1812), Thomas Sutherland (1785–1838), J. Hill, and Harraden (aquatint engravers)[1]](https://monitortribune.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022-02_Microcosm_of_London_Plate_006_-_Auction_Room_Christies_colour_1-768x577.jpg)