Nadine Hall’s Reclamation and Remembering

A few weeks ago, while on a layover in Miami, I had the opportunity to view the Jamaican artist Nadine Hall’s MFA thesis exhibition, entitled Reclamation and Remembering: Ode to the Building Blocks of My Narrative, at the University of Miami exhibition gallery in the Wynwood Building.

Nadine Hall, who was born in Kingston, is a 2015 BFA graduate of the Edna Manley College, in Textile and Fibre Arts, and she went on to do her Master of Fine Arts degree in Sculpture in the Department of Art and Art History of the University of Miami. Hall is not unknown to Jamaican audiences: she was one of the artists in the 2019 Summer Exhibition at the National Gallery of Jamaica, with an ethereal but haunting fibre sculpture installation that spoke about Jamaica’s troubled masculinities and the sexual violence inflicted on women, and she will be in the upcoming Kingston Biennial with recent work.

Hall has already participated in several exhibitions in the USA, and her work is currently on view in the MFA Showcase at the Bonnier Gallery in Miami. She is also associated with the Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator, a Florida-based initiative that supports and promotes Caribbean diaspora artists and that is led by Rosie Gordon-Wallace, who is also Jamaican. Gordon-Wallace was part of her thesis committee, which also included Erica Moiah James, a professor of Art History at Miami University who was previously the director/curator of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas.

Nadine Hall’s MFA exhibition, as its title tells us, represents an act of reclamation and remembering, of a personal and family history that is unique to her own experience but also very recognizably Jamaican. It is a history marked by adversity and trauma but, arguably more importantly, it is a history of resourcefulness, resilience and overcoming, of which the exhibition is itself an exponent, as the MFA study process was not an easy one, despite the support she received from the Caribbean community at and around the university. It is, ultimately, as Nadine told me, a celebration of self and of family, even though there are references to trauma.

The concrete building block is one of the central metaphors in the exhibition. Nadine’s great grandmother, Abihail Bogle (a descendant of Paul Bogle who farmed in St Thomas), was one of the first person in her community to own a concrete house, a proud symbol of her industriousness and determination to overcome the odds of poverty and personal and social stagnation. Building a concrete house, or an extension to such a house, is part of the ambitions of many Jamaicans, and often implemented in an informal, phased manner, when money is available, and stacks of concrete blocks and other building materials for such projects can be seen throughout the island. Likewise, the production and selling of traditional confectionaries, made from local products such as cane sugar, grated coconut, and peanuts, has been a staple cottage industry in the island, and part of the sort of determined, culturally grounded entrepreneurship that has helped to feed many families and send children to school. Making and selling such confectionaries is, in fact, part of Nadine Hall’s own story, as she made and sold coconut drops and other treats to put herself through high school, using recipes that had been handed down in her family.

The concrete block and the traditional confectionaries are rich metaphors for the acts of self-fashioning and transcendence that characterize the stories of the Jamaican people, and Nadine Hall has conjoined the two in her MFA project, by making life-size “concrete blocks” from sugar, coconut, and peanuts. As Nadine puts it in her artist statement: “The symbolic significance of these confectionary blocks – as art objects and metaphor – bears witness, not only to my own narrative of survival, but also that of my great grandmother Abihail Bogle, whose character and life as a farmer, inspired the concept of this exhibition. Within the broader discourses of reclamation and remembering, this installation pays homage to the women who survived the Middle Passage, slavery, and colonialism. Women who, through absolute determination, ingenuity, and resilience – laid the foundation – the building blocks of existence, on which generations are able to build.”

The resulting exhibition is a powerful example of what the American literary theorist Stephen J. Greenblatt has called “resonance”, the capacity of often modest but carefully selected and placed objects to transcend themselves and to evoke and tell bigger stories, appealing powerfully to the emotions, senses, and imagination in doing so. Resonance is at work in the personal mementoes we keep, and it is also an effective strategy in art and exhibitions. A simple shackle exhibited in a museum can evoke the entire history of slavery, and of the human beings who were brutalized and displaced, and the stacks of hair and shoes seen in Holocaust museums, likewise, tell stories of genocide and the individual lives that were disrupted. It is a strategy that is used in a lot of contemporary art, especially in installations. It is visual and material poetry in action.

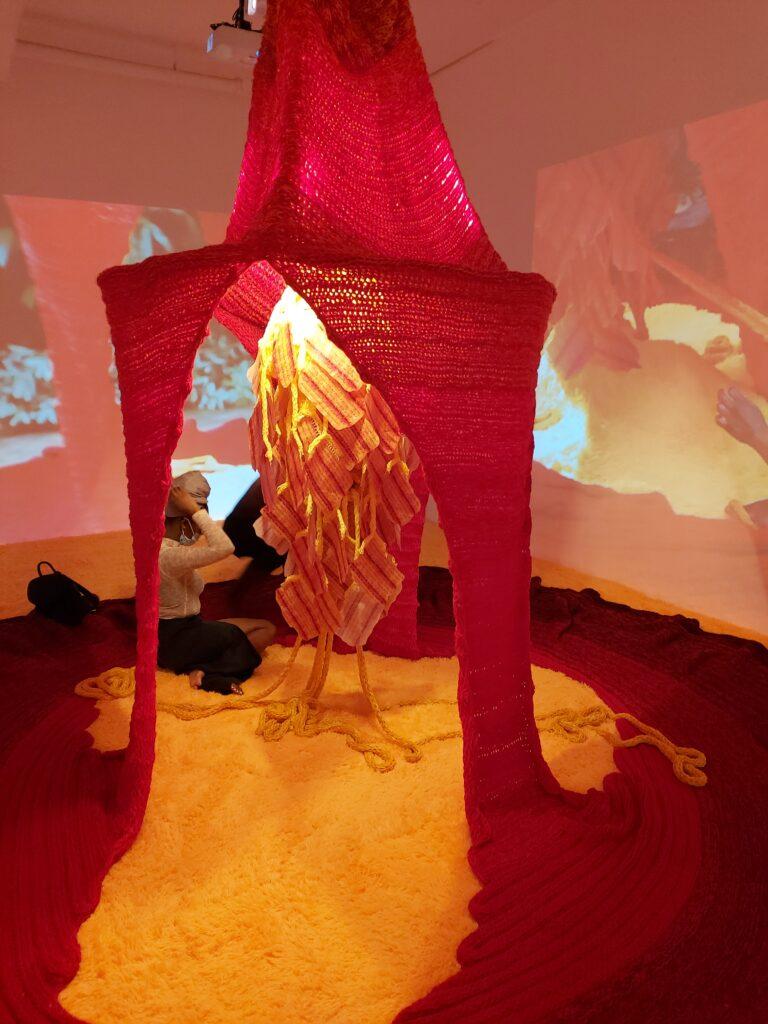

Nadine Hall’s Reclamation and Remembering exhibition takes the form of a large, immersive installation and consists of smaller, altar-like setups and objects that are placed in configurations that tell her stories simply but eloquently, with many layers to be uncovered. The confectionary blocks are the recurrent and defining element, but other objects also appear: husked coconuts; the metal contraptions she fabricated to husk them; machetes and a stick with a hook to harvest the coconuts; the wooden moulds she made to cast the bricks; actual concrete bricks, green and weathered as if they had been languishing in somebody’s yard; paving stones made from the same confectionary materials; a display platter with the actual traditional confectionaries; a photograph of her great-grandmother; and collections of found objects such as a collection of “home sweet home” oil lamps and the sort of fine glass and china and decorative objects that grace many family “what-nots” in Jamaica. There is also an a gilded-frame oval mirror, engraved with the words of Maya Angelou: “Bringing the gifts my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave.”

Nadine Hall’s MFA exhibition is also about making and she went through the whole process from harvesting and husking the coconuts, to making the brick moulds, to baking the confectionary bricks at home, in what echoed the processes used in the Jamaican cottage industries she referenced. This preoccupation on process appeared in the exhibition itself and some of the objects seemed alive, undergoing various unplanned but serendipitous transformations, some of them subtle and others more dramatic: the sugar recrystalized to form glittering layers on the surface of some of the bricks and other bricks oozed a dark red fluid, adding further layers of meaning.

Nadine Hall’s Reclamation and Remembering: Ode to the Building Blocks of My Narrative was a magnificent, deeply moving, and well-choreographed exhibition, rich with personal and cultural significance, great visual beauty, and unexpected but engaging sensory experiences, such as the smells and textures of coconut, cane sugar, and peanuts. I am very glad that I saw it (and grateful that it was held over for a day to facilitate my visit).

Nadine Hall is already an artist to be reckoned with and I look forward to witnessing her future trajectory. I would love to see her MFA show in Jamaica, as it needs to be seen here. As I mentioned in my previous column, it would be an ideal match to Ormsby Hall, the space in downtown Kingston that presently hosts Laura Facey’s exhibition. Not only is Ormsby Hall the perfect space for an exhibition of this nature, but Nadine has personal history in the community and used to take the bus to go high school across the road. It would be a “homecoming” on so many levels.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She lectures at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica, and works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.