Letter from Haiti: Gingerbread Houses and Soupe Joumou

I am nearly halfway through my five-week stay in Haiti to work on a project for Le Centre d’Art. Visiting Haiti at this time is interesting, to say the least, and many people in Jamaica had advised me not to go, because of what has been a wave of kidnappings and other forms of gang-related violence, the breakdown of government, and poor COVID-control practices. The problems are very real and have curtailed our ability to move around. There are, however, efforts to restore law and order, and on those few nights that we have been out we saw more police patrols and checkpoints than I have ever seen on the roads in Jamaica.

Being here has driven home that the reporting in the international media presents a one-sided and often-sensationalized picture, which is a long-standing problem with how external perceptions of Haiti are shaped. There are many things that are going well in Haiti. The bustling Centre d’Art is one example. And, despite all the challenges and disruptions, Haiti continues to be a cultural powerhouse in the Caribbean with its culture being a primary source of resilience.

There is, also, a healthy and widely shared respect for, and pride in, the country’s history and cultural heritage, which is supported by well-informed action, such as the inscription of various aspects of Haitian culture on UNESCO’s and other world heritage lists – a strategy which has helped Haitian cultural organizations to attract major international grants. The “Soupe Joumou,” a hearty pumpkin beef soup traditionally eaten on 1 January, Haiti’s Independence Day, and symbolically associated with Haiti’s revolutionary quest for liberty, was recently inscribed inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. We tasted it on our arrival, and it is a recognizably Caribbean meal soup with a unique Haitian flavour and history. Food can, indeed, be about far more than nutrition.

Our hosts put us up, with appropriate security of course, in a gingerbread mansion in the Pacot neighbourhood, part of the Gingerbread District of Port-au-Prince. These houses, which can also be found in other Haitian towns and cities such as Jacmel and Cap Haitien, are well recognized as an important and defining part of the country’s architectural heritage. They are a source of national pride, a tribute to Haitian craftsmanship and creativity, and a reminder of a more affluent past that affirms that better futures are possible. The Port-au-Prince Gingerbread District was, in 2010, added to the World Monuments Watch List, a process that had been initiated several months before the earthquake. This turned out to be an inspired move as it set the stage to receive international assistance with the restoration of what was already, before the earthquake, threatened heritage (the district was again added to the World Monuments Watch List in 2020). While some gingerbread houses suffered serious damage, and had often been neglected over the years, most performed much better than their concrete counterparts, which also illustrated that traditional, tried-and-proven technology is often more resilient in such circumstances.

While comparable in form and style to other gingerbread styles in the Caribbean, Jamaica included, the Haitian buildings stand out because of the hybrid, playful, at times gravity-defying designs that give the buildings a surreal, fairy-tale like quality. The structures are timber-framed, typically with thick brick and stone walls on the ground floor and wood on the upper floors. Elaborate carved wood decorations, such as fret- and lattice-work and carved cornices, and elegant forged and cast metal work are also common, along with pressed metal ceilings. Despite the thick walls on the ground floor, the structures are very open and airy, with high ceilings, louvred doors and windows, multiple porches and terraces, and excellent cross ventilation, but they can also be closed securely with heavy wooden shutters.

One of the oldest such structures is the storied Oloffson Hotel, with its lace-like fretwork. Presently closed, the hotel, during its heyday accommodated many celebrity visitors, such as Elizabeth Taylor, and Mick and Bianca Jagger, and was once the site of lively entertainment, from the famous Vodou-inspired floor show to the Thursday-evening performances by the RAM band, which was led by the hotel proprietor and musician Richard Morse. The hotel had, in the 1960s, served as the inspiration for the Hotel Trianon in Graham Greene’s The Comedians (1966), an acerbic narrative about Haiti during the violent dictatorship of “Papa Doc” Duvalier. The 1967 film version, headlined by Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Alec Guinness, Peter Ustinov, Cicely Tyson, and James Earl Jones, was shot in Benin because of the deteriorating political situation in Haiti, where the book was, furthermore, blacklisted by the Duvalier regime.

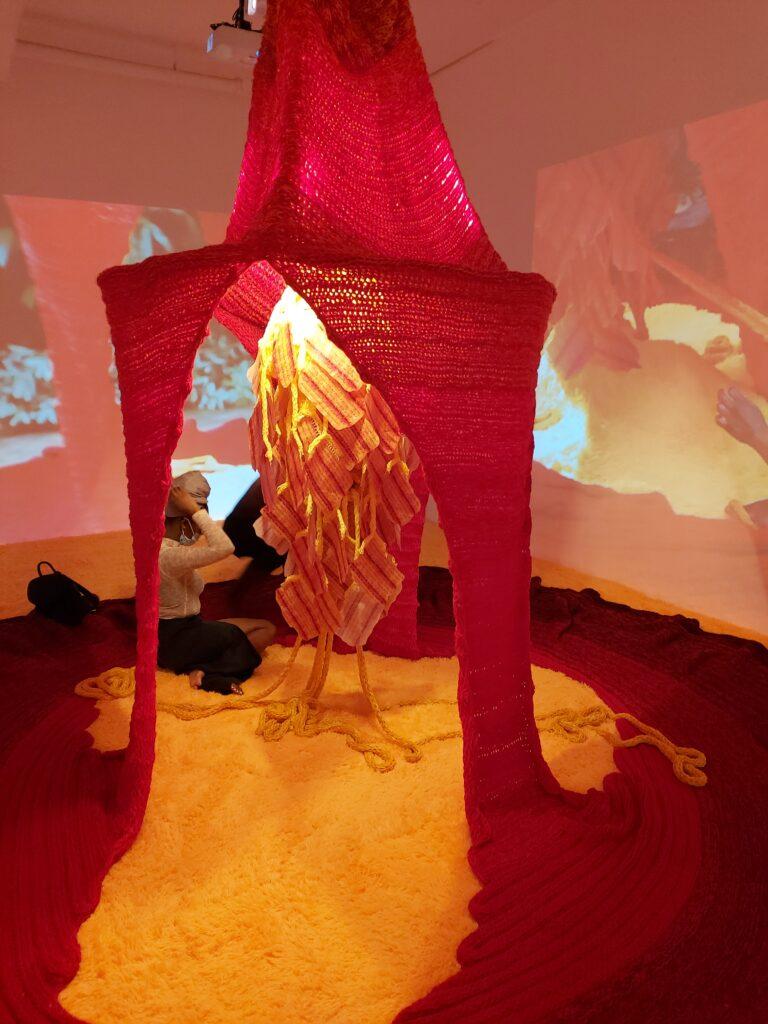

When the Soupe Joumou was declared by UNESCO,Haitian novelist and poet, Lyonel Trouillot, wrote a scathing rebuttal for the Guardian in which he cautioned against romanticising Haiti’s history and culture at the expense of recognizing and tackling its very real social and political problems. This word of caution also applies to the Gingerbread house heritage. Haiti’s Gingerbread houses are a rightful source of national pride, and a living tribute to Haitian craftsmanship, ingenuity and creativity. Several of the structures have been put to public use in ways that are beneficial to the broader community, such as the Maison Dufort, which serves as a facility for art events and exhibitions, and the Maison Chenet, which will become a library. Both were restored by FOKAL, an influential Haitian civil society organization which is deeply involved in social and cultural development projects.

We should, however, not gloss over the gingerbread mansions’ association with wealth and privilege, as they were owned by wealthy merchants, agricultural entrepreneurs, politicians and professionals, and embody the postcolonial class structures and deep social divisions that have plagued Haiti since the Revolution. The houses are often named after the prominent families that owned them, such as Oloffson and Larsen, which are notably un-Haitian. This reflects the inflow of European migrants who were in search of business opportunities in the nineteenth and early twentieth century Haiti.

Look out for another Letter from Haiti next week, on Vives, an exhibition of work by Haitian women artists from Le Centre d’Art’s collection at the Maison Dufort.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She lectures at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica, and works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.