African sensitivities and the transatlantic slave trade

The act of chattel slavery has been visited over and over again by continental Africans and Black Diasporans; the latter comprising mainly African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Impressive scholarly works abound on the realities of chattel slavery which address areas such as the various territories that witnessed the capture, sale, revolts, executions in Africa and the Americas. A troubling issue is the belief among some Black diasporans that continental Africans do not consider the transatlantic slave trade and slavery as events that deserve much attention. Such persons are offended by what they find to be Africans’ insensitivity to the slave trade.

I think that many Black diasporans do not appreciate that race, racism and its manifestations and consequences are not perceived or handled in the same manner by Africans and Black Diasporans. There is no doubt that these three factors are of vital importance to Blacks in the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe and other parts of the world where Black diasporas exist. For instance, African Americans live in the constant fear of the cruel and brutal repression meted out by White America. The mass incarceration of Blacks in the US, and on the other side of the Atlantic in general, makes it obvious, and that “black-phobia” emerged out of historic injustices and barbaric acts like the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, one of the most telling manifestations of the vulnerability of Blacks in America. Black Lives Matter is the most recent of such socio-political movements.

Jim Crow and its consequences are still present in education, access to health care, and so on. All these contribute to making the slave trade a permanent and indelible horror that Black diasporans live with. Racism, race-based violence, and injustice motivate many of them to symbolically return to their roots, or to re-connect with their “Africanness” through trips to Africa, rebaptizing themselves and taking African names and dropping those imposed on them by slave masters. African couture and dressing style, African languages, dances are, therefore, embraced as expressions of lost identity, one’s soul by Blacks in the diaspora. In addition, pilgrimages are made to the slave castles on the West African coast. Cape Coast Castle and Elmina Castle in Ghana and the island of Gorée in Senegal are the main ones, known to and visited by those returnees who experience high emotions during such trips.

Now it is not accurate to say that continental Africans do not regard the transatlantic slave trade with much importance or seriousness. What cannot be denied is that Africa and the Black Diaspora have gone through experiences that are different and, as a result, the Black race on the continent and outside the continent, especially in the diaspora react differently to issues of race, racism, and racial segregation. Sadly enough, civil wars, lack of national development, postcolonialism, famine are terms and cases that resonate with life in Africa, more than the slave trade and its repercussions. That does not mean that slavery and its horrible aftermath is discounted by Africans; it simply means that those difficulties which are part of the daily life of the Black Diasporan are not recurrent in the life of continental Africans. One can even say without any doubt that Africans are also preoccupied with the transatlantic slave trade. Vivid illustrations of that consciousness lie in a close observation of the slave castles on the West African Coast, and what happens inside those castles. While Black Diasporans see in those castles the perfect illustration of the beginning and continuation of their suffering let us also be mindful of the efforts that Africans put in keeping those slave castes and running them in such a way that the slave trade is permanently engraved in the psyche of the African, the peoples on whose soil those forts are located. The tour guides are very familiar with all the details of chattel slavery and take Black Diasporans, and anybody who desires to know, through a thorough journey, by way of lecture, demonstrations and explanations, of the history of the slave forts. “Visitors” are allowed to enter the prison cells, to experience how it feels to be caged in such “holes”.

Many other slave forts abound on the coasts of Ghana and more and more slave castles are being discovered and appreciated by Africans and Black Diasporans: while Christianborg Castle in Osu, Accra is well known, Fort Good Hope in Senya, near Accra is being brought to the attention of the international public as is Fort Amsterdam in Koromantin (Central Region, Ghana) and their function as the most important structures in the transatlantic slave trade is exhibited and coherently linked to the current Black consciousness, both in Africa and in the Black Diaspora.

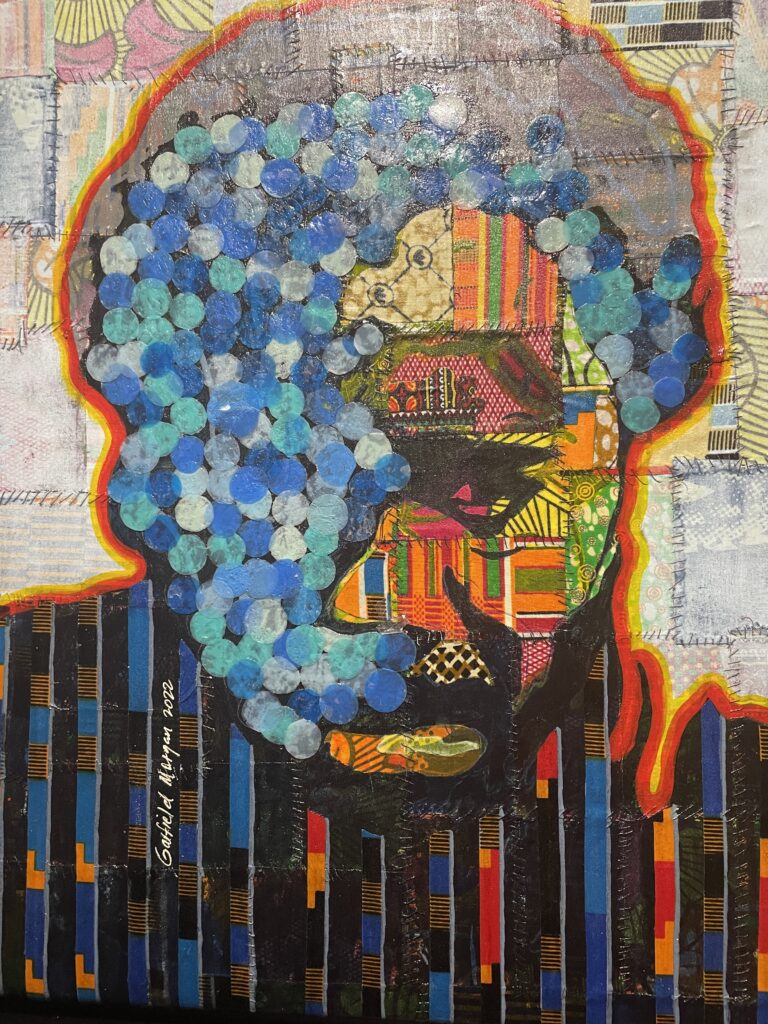

Projects that deserve praise and ovation, which represent the angst shared by continental Africans regarding the slave experience, are the current works of the Ghanaian film maker Kwaw Ansah whose Bisaberewa Museum in Sekondi (Western Region, Ghana). This museum was created as “one of the largest sculptural representations in clay, wood, cement, paintings and photographs of personalities whose sacrifices have shaped African history, both within the continent and the diaspora”. It was officially inaugurated in July 2019 and has about 2,200 artefacts, sculptural pieces and photographs of heroes of the African struggle and the African American Civil Rights Movement as well as other Black personalities in the French, Portuguese and Spanish Caribbean. These representations capture events within the slave dungeons in Africa, the toils of the Africans on the slave plantations and highlight activities of the Civil Rights Movement culminating in the election of the first African American President of the US. This artist attaches inestimable value to the Arts of the Black world. He is interested in anything pan-African. He has been collecting and preserving African art as far back as he can remember, as he says and his attachment to African and African American life and values lies in his founding of Pan-African TV in Ghana, which is dedicated to preserving the history of the Black Race, promoting African values and celebrating Pan African heroes.

Another laudable Black life project is the Nkyinkyin Museum of Ada Foha in Ghana. Built in 2011 by artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, it is one of the biggest outdoor museums in Ghana and recreates the slave trade with an exact and surreal touch – the chained busts and heads of slaves – some moulded in concrete and others with clay – sit on a muddy land, adjacent to a water body where other “craftily reconstructed” slaves have started their journey on the sea. The finished works can be seen at Nkyinkyim Museum and what reiterates the diasporan dimension of this Ghanaian museum is that some of those sculptures are found at the Legacy Museum Montgomery Alabama, USA. The Kyinkyin symbol means “twisted” and this project aims at capturing the twists and turns in African history. It is important to point out that both the Nkyinkyin and Bisaberewa museums are privately funded. They are made and preserved with the money of persons like Kwaw Ansah, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo and likeminded people.

Moussa Traoré is Associate Professor at the Department of English of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana.