Gaston Tabois memoir part 2

Last week, we looked at the early career and work of Gaston Tabois. In this second, concluding section, we look at his later work, and the reception of his work.

It is often assumed that self-taught, intuitive artists have a fixed, innate style which is immune from outside influence. Interactions with the market and, particularly, with tourism are often deemed inherently corrupting and something from which such artists must be sheltered, even though their livelihood often depends on it. There were, in fact, such concerns about Gaston Tabois’ work as it evolved. The critic and collector (and later diplomat) Norman Rae, for instance, wrote in Ian Fleming Introduces Jamaica (1965) that “Gaston Tabois once charmed with his fresh, naïve, gaily primitive vignettes of country and city life, but he found it hard to recover after Elizabeth Taylor had bought some of his work”.

Looking back, it is clear Tabois “recovered” just fine from his brush with celebrity patronage but there is no doubt that his style changed significantly in the 1960s and 70s, while the range of his subject matter also expanded with portraits, for instance, becoming more common. It, however, seems that these changes were driven less by market-pressures than by Tabois’ desire to develop his artistic skills, and to engage with concurrent developments in mainstream art. While a full evaluation of his work from that time is yet to be conducted, it seems fair to say that it has a more experimental quality, with the inevitable hits and misses.

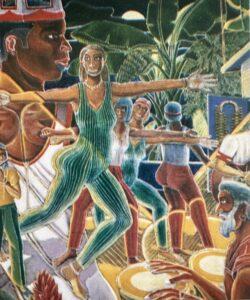

By the early 1980s, he had settled in his highly recognizable later style, which was characterized by greater compositional clarity, less texture and detail, and a quasi-transparent luminosity, which gave his paintings and watercolours an almost stained glass-like quality, although the spatial distortions and surreal undercurrents remained. He continued painting scenes from daily life, rural and urban, and the occasional portrait, but there were also fanciful historical scenes, tributes, a few religious images, and even some bountiful “pin-up” nudes. One of his nudes was actually stolen from the Hills Gallery in 1971.

David Boxer recognized the development in Tabois’ approach and did not see his desire to improve his artistry as an obstacle to his “legitimacy” as an Intuitive. In fact, he made light of Tabois’ ambition to join the tradition of the “masters” and interpreted his statement that “the painter of the Mona Lisa” was a key influence, without mentioning the artist’s name, as evidence of his remove, rather than proximity, to the mainstream.

Gaston Tabois was, however, uncomfortable at his classification as an intuitive. I spoke with him about this in 2001, in a series of interviews which also involved Everald Brown, Ras Dizzy and Leonard Daley. While the others saw the designation as appropriate and generally beneficial to their artistic career, Tabois was the only one to object. He argued that the designation “Intuitive” had been an obstacle to his desired ascent into the hierarchies of the Jamaican art world, which was an unexpected but insightful observation.

The intuitives category, indeed, involves unacknowledged assumptions about the social identity of the artists in question, as being from a deep rural or inner-city background and lacking in formal education or awareness of mainstream art, and that did not sit easily with Tabois’ social background as a member of the emerging middle class. The label also assumes the artist’s willingness to “play along” with the asymmetrical patronage dynamics that have surrounded Intuitive art and to subject themselves to the sort of controlling, from-the-top-down patronage that has shaped that field, which is something that Tabois obviously resisted and even resented.

In Tabois’, admittedly, unique case, however, it is the work itself, and its consistency with conceptions about “naïve” art, far more so than the person, that determined his sustained classification as an intuitive, although that understates the complexity of his work. But there is no doubt that the intuitive designation prevented Tabois from using his more advantageous social background to get “up there with Barrington Watson,” as he put it during our interview, in terms of his professional empowerment and social standing.

While his concerns certainly had merit, Tabois did receive significant national recognition during his lifetime and he is widely regarded as one of the most important Jamaican intuitives. He regularly exhibited at the Institute of Jamaica, where he had a solo exhibition in 1962, and, later on, at the National Gallery of Jamaica, in the Annual National and National Biennial exhibitions. He was one of only a few artists to be featured in the National Gallery’s three specialized intuitives exhibitions, namely Intuitive Eye (1979), Fifteen Intuitives (1987) and Intuitives III (2006), and he was included in the Jamaican Art 1922-1982 exhibition, a major survey exhibition which was toured in the USA, Canada, Haiti and, ultimately, Jamaica, by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service from 1982 to 1986.

Tabois also received the Institute of Jamaica’s Bronze and Silver Musgrave awards in 1992 and 2010, respectively, and was honoured with a small tribute exhibition on the occasion of the latter in the 2010 National Biennial. Two of Tabois’ most iconic paintings were furthermore featured on Jamaican postal stamps: Road Menders was, in 1986, included in a set of four stamps dedicated to the Intuitives that also featured work by John Dunkley, Kapo and Sidney McLaren, and John Canoe at Guanabo Vale, another early work was, in 2002, used in that year’s Christmas stamp issue.

Unless their work is actively exhibited and written about, artists, however, quickly drop out of view, no matter how popular they were during their lifetime, and there is some concern that this is already happening with Tabois and other Jamaican artists of his generation. A comprehensive, in-depth assessment of Gaston Tabois’ work is now long overdue and should, ideally, involve a retrospective exhibition and a well-documented publication.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. The second, revised and expanded edition of her best-known book “Caribbean Art” was recently published in the World of Art series of Thames and Hudson. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.

![Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and Augustus Charles Pugin (1762–1832) (after) John Bluck (fl. 1791–1819), Joseph Constantine Stadler (fl. 1780–1812), Thomas Sutherland (1785–1838), J. Hill, and Harraden (aquatint engravers)[1]](https://monitortribune.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022-02_Microcosm_of_London_Plate_006_-_Auction_Room_Christies_colour_1-768x577.jpg)