New study reveals HPV vaccine effects on cervical cancer

A single dose of the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV) is highly effective at preventing infections over three years, most likely lowering rates of cervical cancer and other diseases linked to the virus, according to a new study in Kenya. According to the media release, the single-dose strategy would extend supplies of the vaccine, lower costs and simplify distribution, which would make vaccination a more viable option in countries with limited resources, experts said.

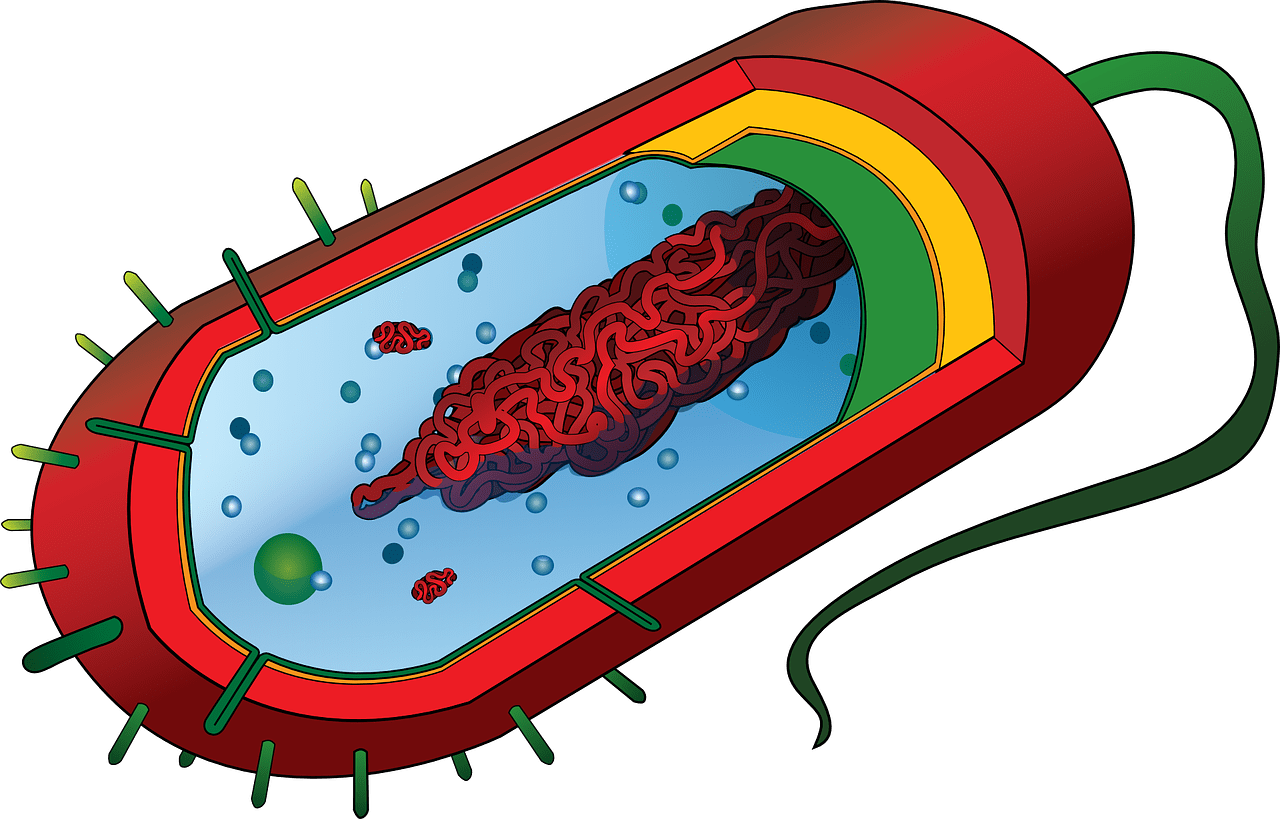

HPV is a sexually transmitted infection linked to cervical cancer and other health problems. Health officials in many countries recommend two doses of the vaccine for adolescent girls younger than 15, and three doses for those who are older. But observational data has long suggested that a single dose offers effective protection against HPV for at least a decade. The new results are the first confirmation from a gold-standard clinical trial that a single dose may be as effective as two or three doses, at least over three years. Results of a direct comparison of one- and two-dose regimens will not be available until 2025.

At least 24 countries, including Mexico, Tonga and Guyana, have shifted to the one-dose approach, according to the World Health Organization. The new evidence may convince more countries to adopt the strategy. “What we had predicted was that this would be most interesting for the low- or middle-income countries,” said Paul Bloem, a senior adviser on HPV vaccination programmes at the WHO. But high-income countries like Britain and Australia were among the first to change their policies, he noted.

The WHO estimates that if widely deployed, a single-dose strategy could prevent 60 million cervical cancer cases and 45 million deaths worldwide over the next 100 years. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer in women globally, with an estimated 604,000 new cases in 2020, according to the WHO. The disease killed an estimated 342,000 women in 2020, more than the number who died during pregnancy or childbirth. “This is a real killer of women,” said Dr. Seth Berkley, chief executive of Gavi, which funds immunization programmes in lower-income nations. “It is also a disease that really kills women in the prime of their lives,” he added, “and does it in a really horrible way.” More than 95 per cent of cervical cancer cases is caused by sexually transmitted HPV. Multiple strains of the virus are prevalent, but subtypes 16 and 18 are responsible for 70 per cent of cervical cancers.

The HPV vaccine debuted in 2006 and is a “near-perfect prevention intervention for cervical cancer and other HPV-associated cancers,” said Dr Ruanne Barnabas, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, who led the new study.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine that year in the United States, and since then infections with the viral strains that cause cancers have decreased by more than 80 percent in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.